Alternative Archeologies:

Archives of the Indus, Inferior Bodies, and Labor Relations at MohenjoDaro

The site of MohenjoDaro is located in contemporary Pakistan in Sindh Province and is considered one of the main urban centers on the Harappan landscape, extending well over 100 hectares, with some arguing for the extension of the site to up to 250 hectares.1

For a hundred years this site has lived within Sindhi cultural memory through song, poetry, literature, and internationally through archaeological work. First reported by R.D. Banerjee in 1922 and announced by Sir John Marshall in the Illustrated London News in 1924, MohenjoDaro became part of the international public, specifically part of the British public. Major excavations at the site took place between 1926 and 1931, directed by Ernest Mackay.

Due to this practice a distinction was created between what was considered locally relevant and what was of international significance. Utilizing excavation reports from the first two decades of work at the site as colonial legacy data, we address the multiple ways by which the documentation of colonial work at this archaeological site violates ethical sensibilities around information, data management, and accessibility. As a way to decolonize this practice, we present ways by which data visualization can undo some of that violence by making the archaeological and archival data accessible.

In particular, the inaccessibility of legacy data informs the approach by creating new ways of seeing archival data.2 One way to practice decolonization while working with legacy data sets is to lift, amplify, and celebrate those who have been rendered invisible. This project aims to do just that.

Traces of the Indus

The archaeological site is located in the semi-arid region of Sindh, situated on a Pleistocene ridge in the floodplain of the Indus River. The ancient city is situated between the Indus to the west and the Ghaggar Hakra on the east, ideal for both trade and farming on the alluvial flood plains.

Utilizing Archaeological Survey Maps from the British Survey of India, contemporary satellite imagery and data from Open Street Maps we can trace the Indus as it moves across the landscape in the past century, leaving behind a geological archive.3

Indus River and the site of MohenjoDaro

Indus River and the site of MohenjoDaro

1920s + 1930s

2020s

Archaeological excavations at MohenjoDaro document hundreds of dwellings and large buildings constructed along streets and lanes oriented towards cardinal points, which index the architectural sophistication of a well-planned city.5 Excavations were the result of the labor of many archaeologists, anthropologists, excavators, and others working and caring for the site.

We recognize that MohenjoDaro belongs to a history of discovery by those who, within a colonial framework, conduct archaeological field study as military campaigns — and as a part of those campaigns, construct and define the site as an archaeological site.7 These campaigns are embedded within systems of governance, specifically colonial governance, and those engaged in that system, replicate the impact of that system by merely participating in it. Heralding tenants of modernity, the Archaeological Survey of India at the time of discovery of the site was the quintessential colonial bureaucratic machine.8

It is within this bureaucracy that we aim to uncover, center, amplify, and celebrate those who otherwise would be overlooked, ignored, or deemed unimportant within the archive. We recognize these folks as those doing the care work on the site.

MohenjoDaro Archive:

Receipts and Correspondence,

1936 - 1946

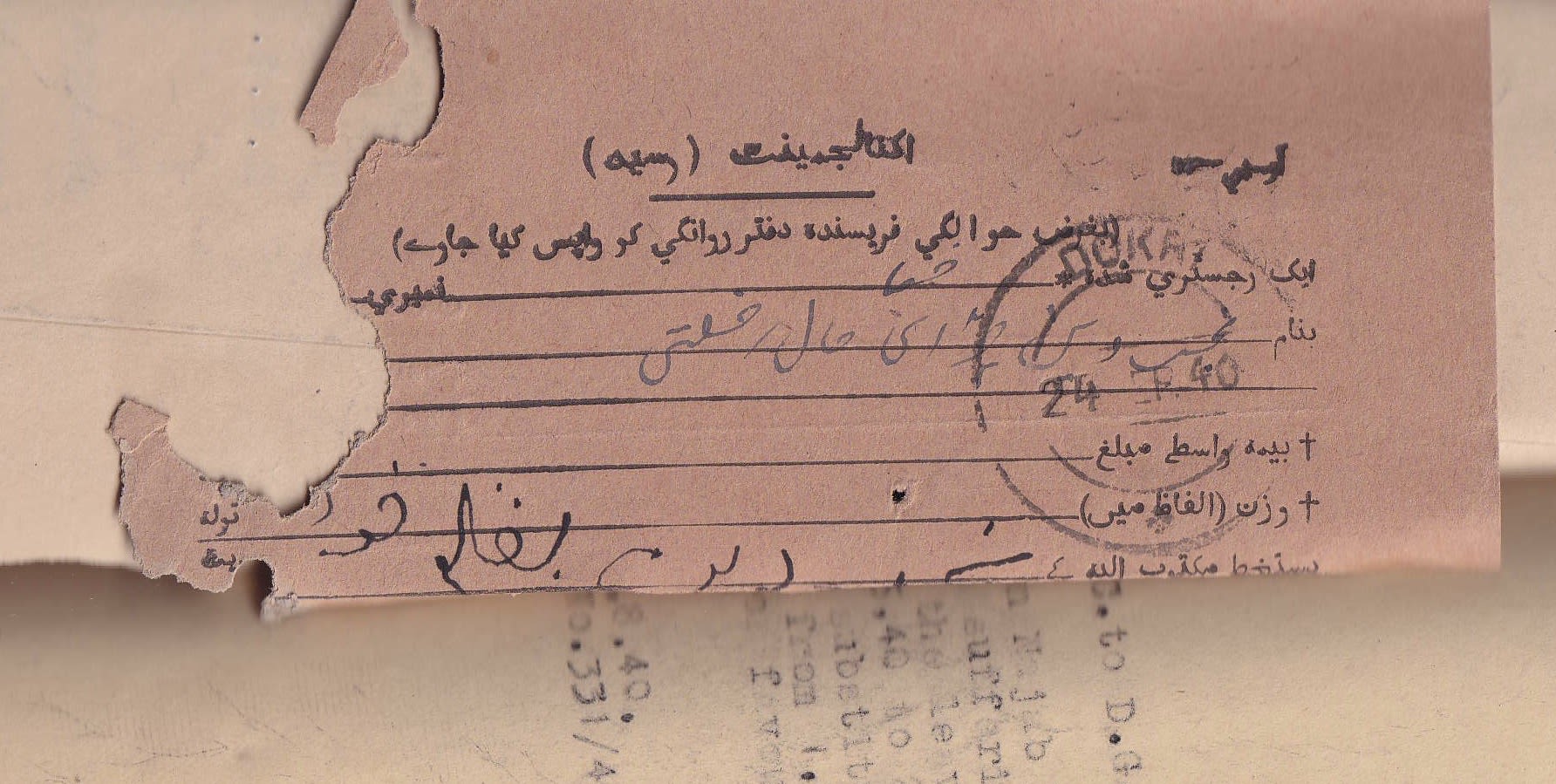

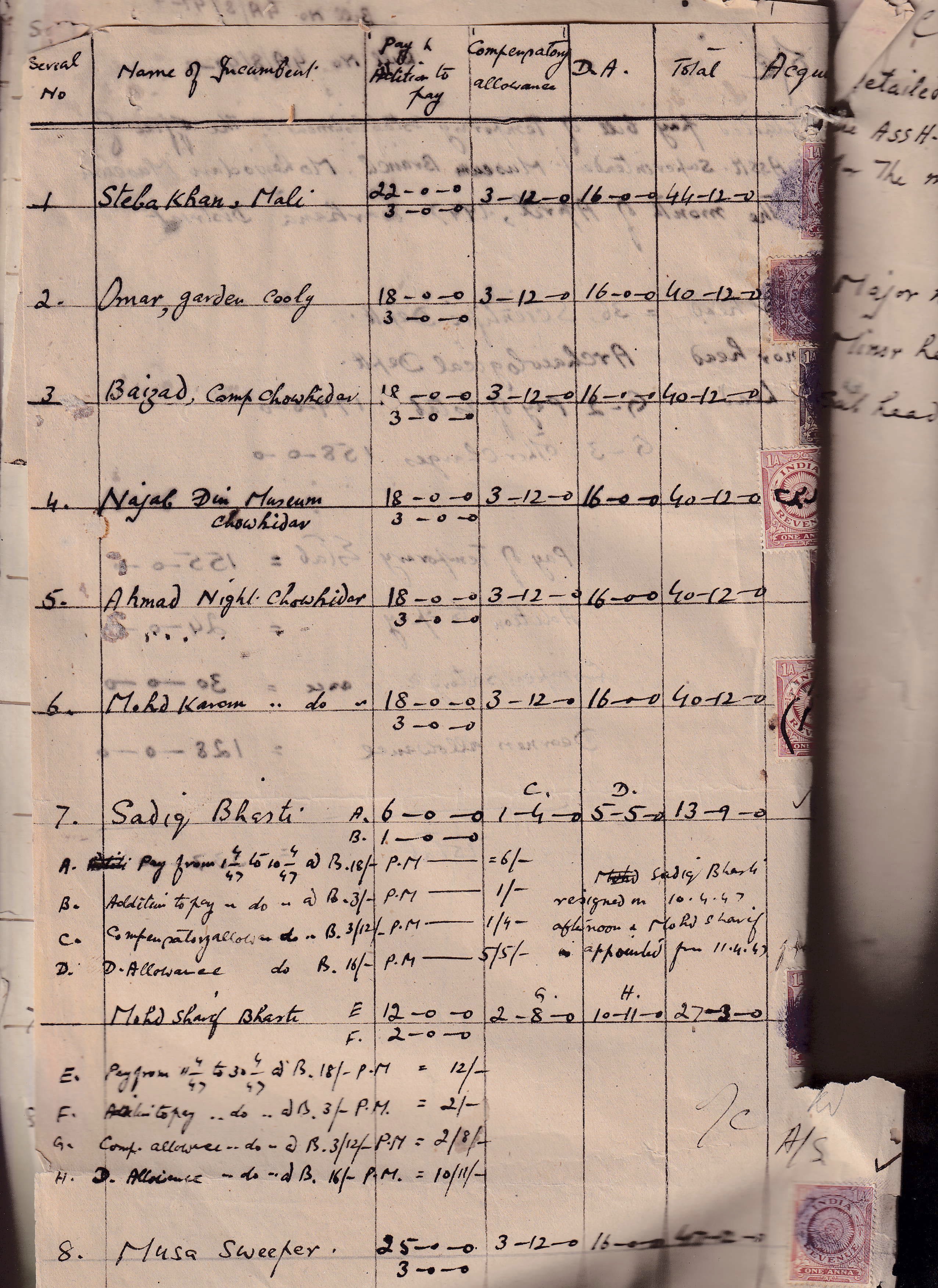

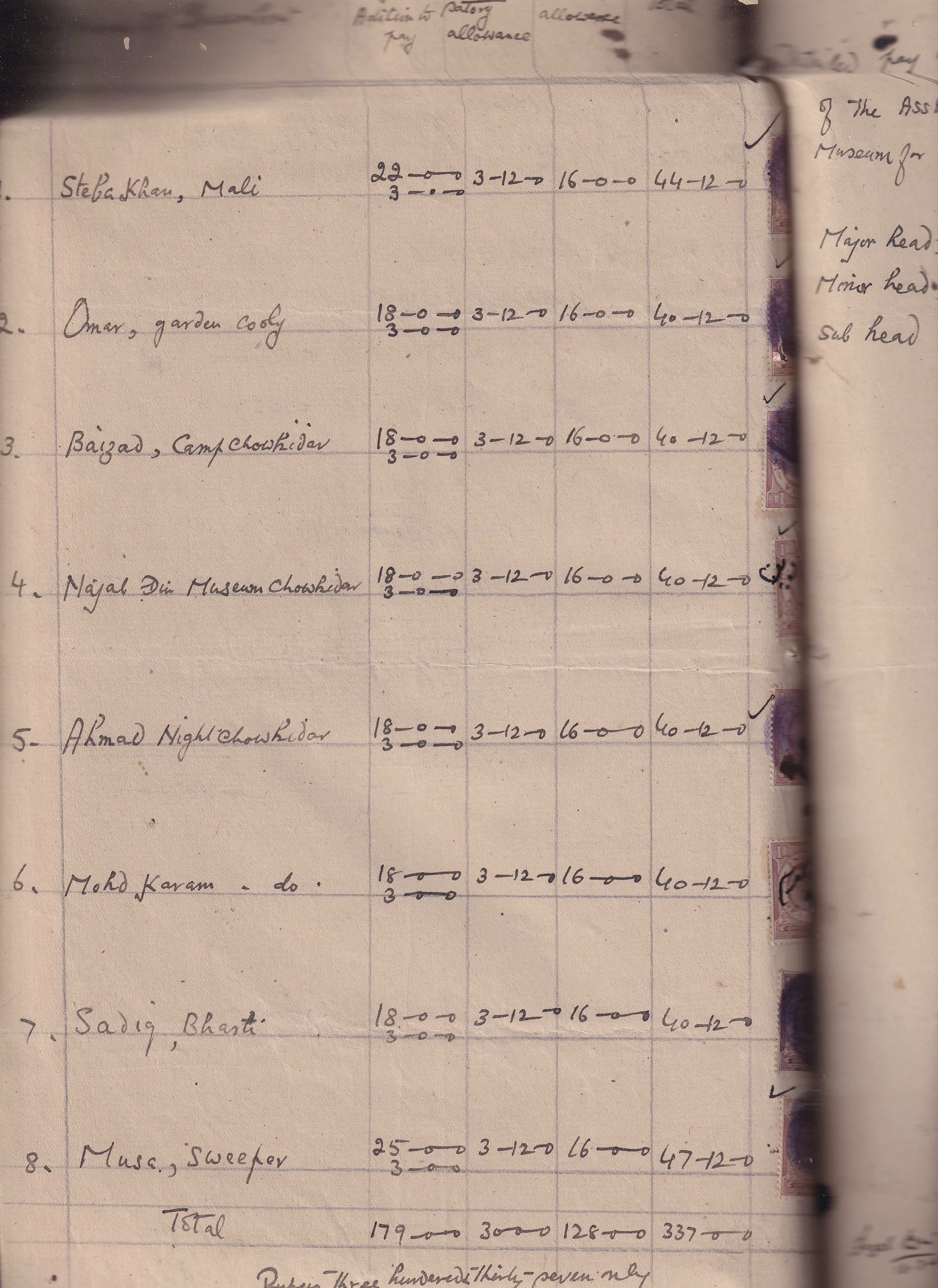

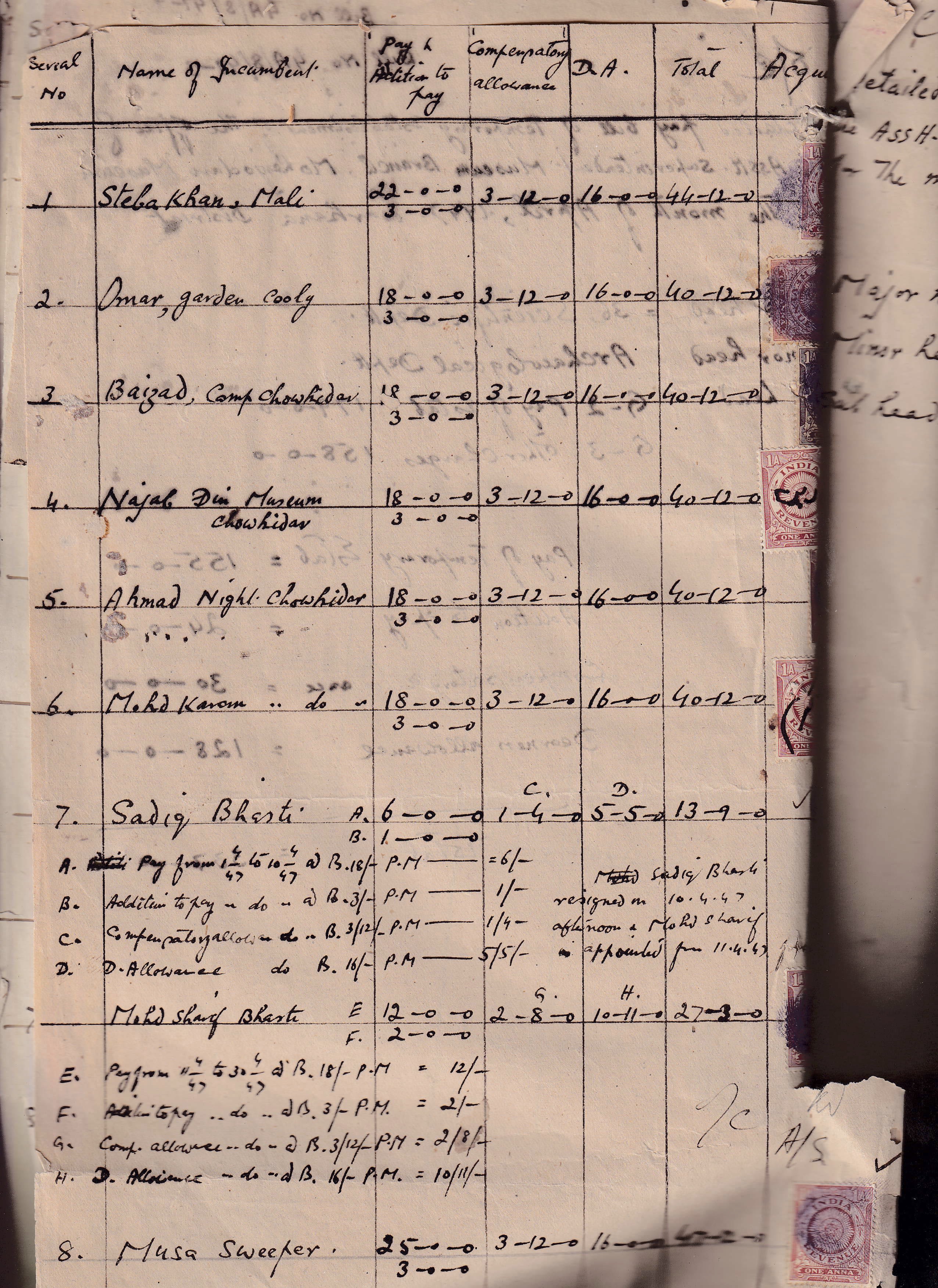

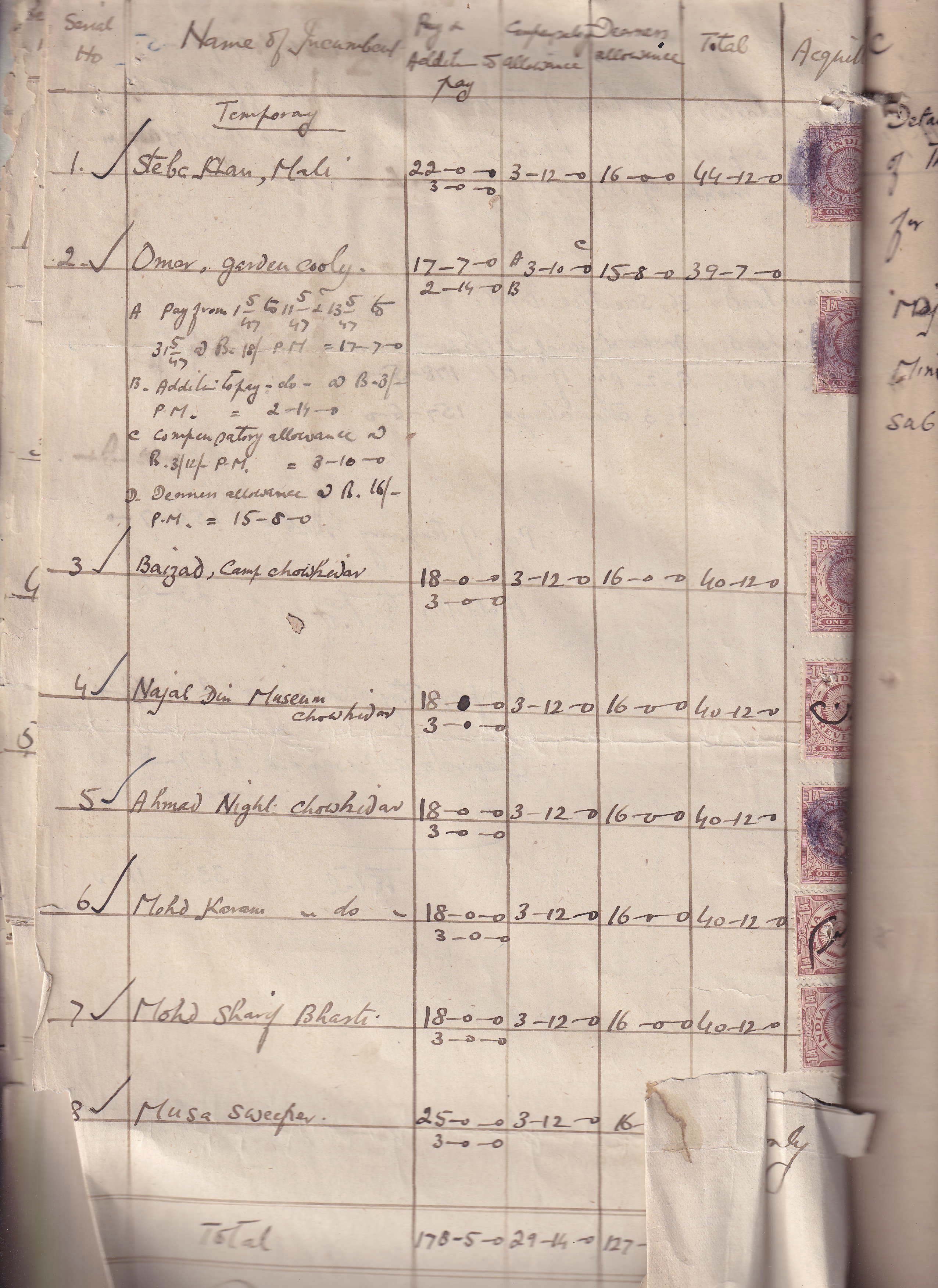

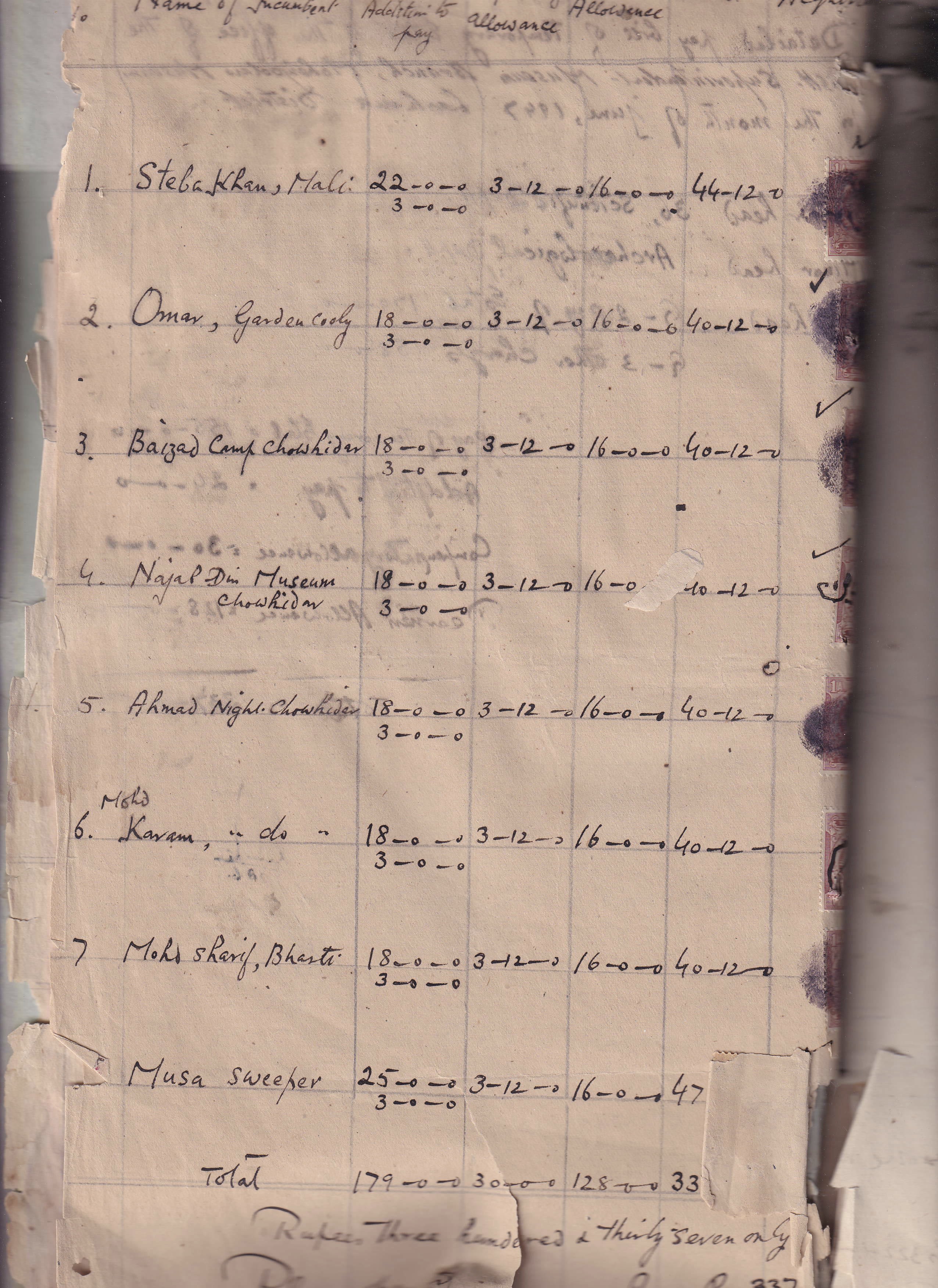

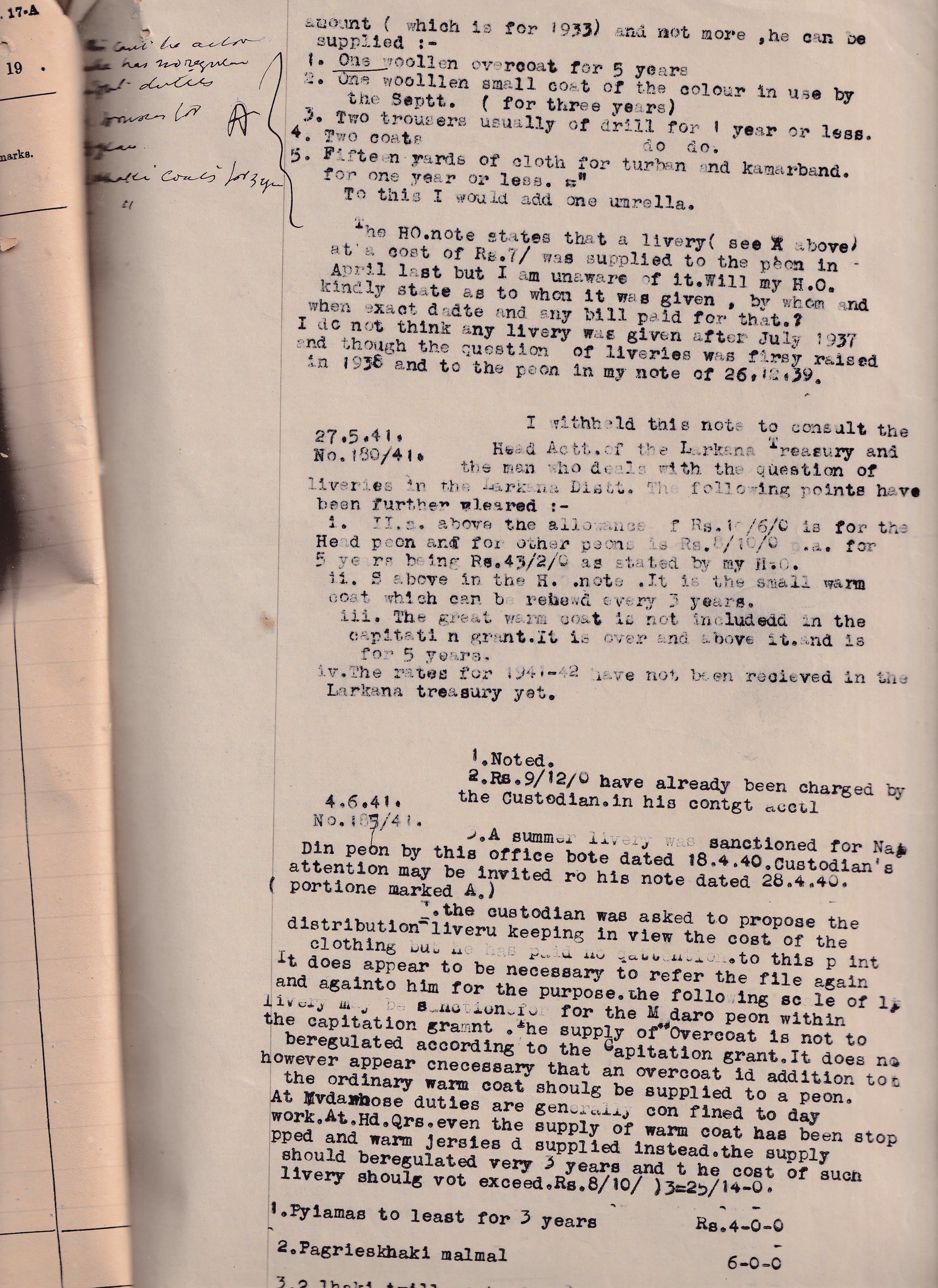

The following images are of archives scanned from the Government of Sindh offices at MohenjoDaro. This particular archive spans 1936-1946, a decade just prior to Partition (1947), and gathers within it the bureaucratic infrastructure put into place through which everyday colonial control is structured and maintained. During this time period, excavations were not actively taking place, but the site and museum were maintained, cared for, and protected. Bureaucratic colonial control is exemplified through the keeping and reporting of money spent. These muster rolls and receipts illustrate the structural holding of bodies in place through the documentation of work done at the site and salaries given to the caretakers of the site. As one moves through the documents, particular names of individuals begin to reoccur. One may approach the archive as one might excavate a trench, and uncover stories about peoples’ lives at MohenjoDaro during the colonial time period.

Labor in the Archives:

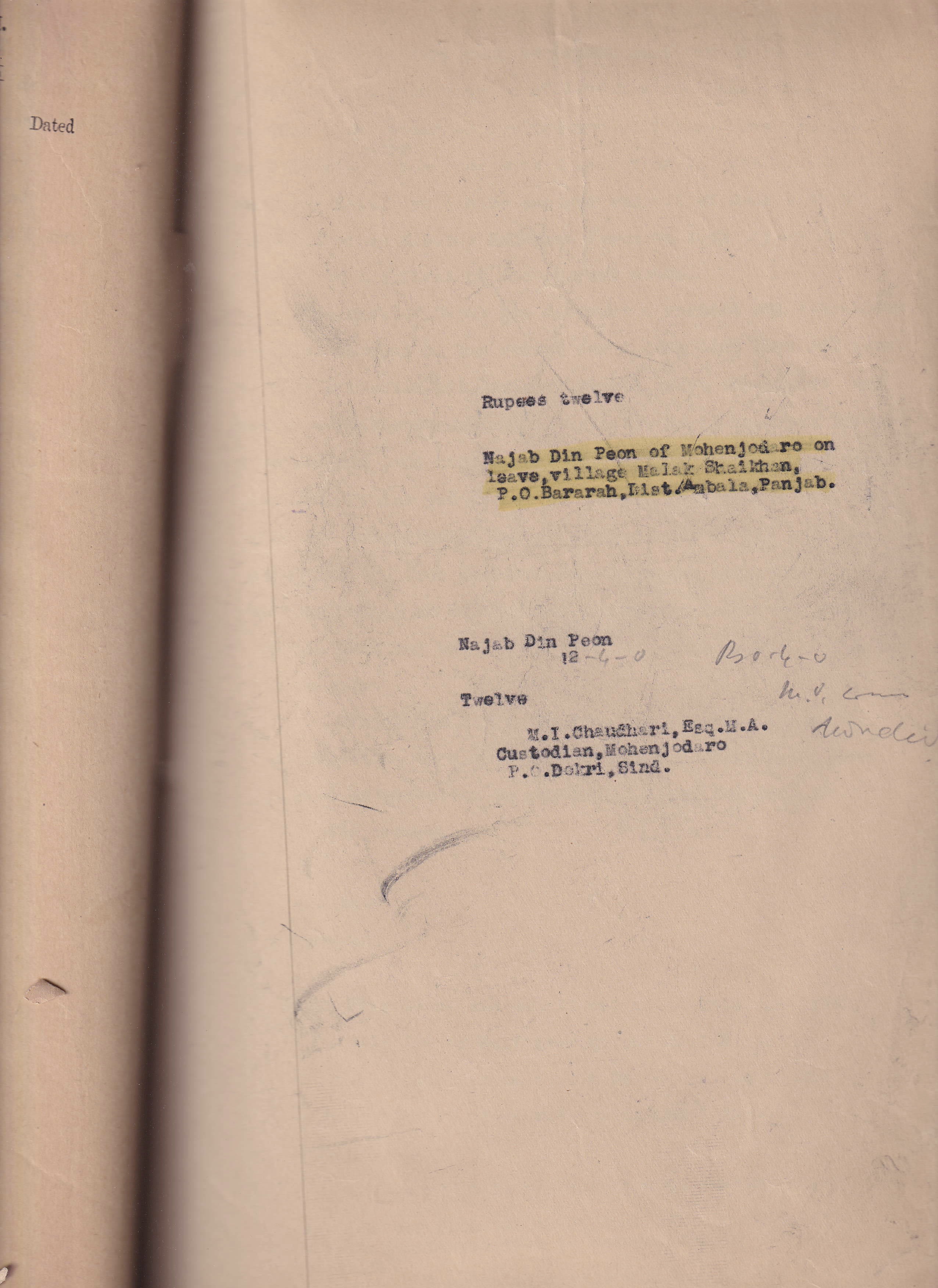

Najab Din

One such emergent story is that of chowkidar, Najab Din. His story illustrates his capacity for self advocacy, his unique talents, and his commitment to the archaeological site. One of our earliest mentions of Najab Din is by Earnest Mackay in 1932, who is hiring Najab Din on a temporary basis because of his high regard for Najab Din’s work. In that same letter, however, Mackay also says that he can be let go without any notice. For any student of labor, the ability to be terminated without notice, or inequitable working conditions, raise red flags. Issues of archaeological labor do not fall within the usual studies of British Colonial Labor as the labor that is often discussed is of the factory worker and the workers within industrial spaces. It did, however, impact the ways by which colonial decision making at the archaeological field house was articulated. As DeSousa argues in "Modernizing the Colonial Labor Subject in India," the colonial project in India countered the labor movements evolving anticolonial consciousness through legal frameworks.9 Colonial labor laws were instruments of governmentality, and it was through these laws that, within India, labor laws aimed to transform the traditional worker to a more modern and efficient laborer. These laws also borrowed heavily from Brahammical sensibilities around what were called, ‘inferior races,’ thus classifying many of the labor in these archaeological camps as ‘inferior servants.’ This phrase, ‘inferior servants’ occurs often within the archival record, as a matter of fact descriptor. The coming together of casteism and colonial rulings is clear in the archive and its impact on livelihoods and treatment of people working at the site.

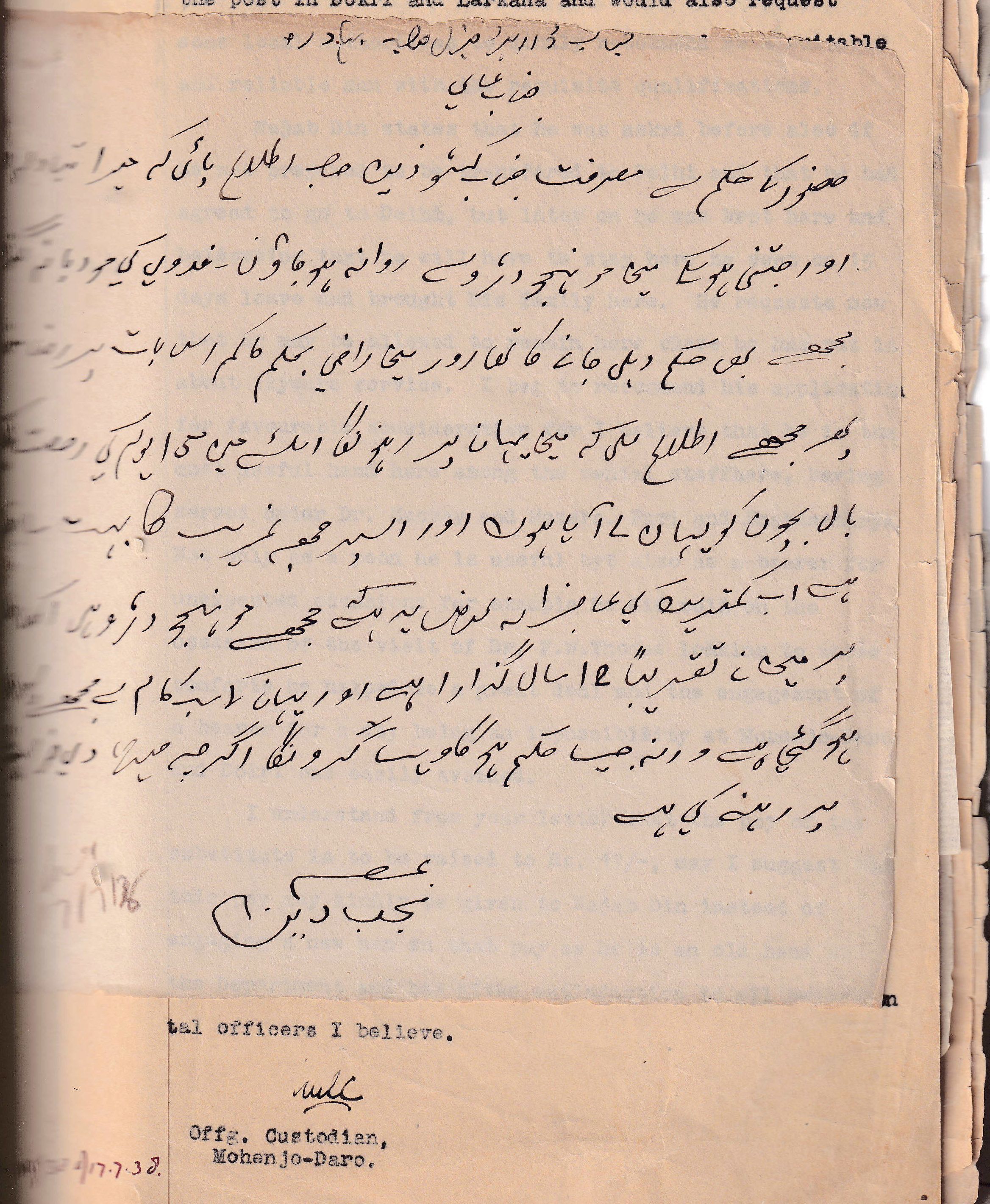

The following archive provides an insight into the ways by which Najab Din negotiated his space within the colonial bureaucracy, continuously advocating for better working conditions. These are the stories that are usually hidden within archival collections. Our aim is to bring recognition to chowkidars like Najab Din, who have worked and lived at the site of MohenjoDaro for a large part of their lives, and should be recognized within the history of the site.

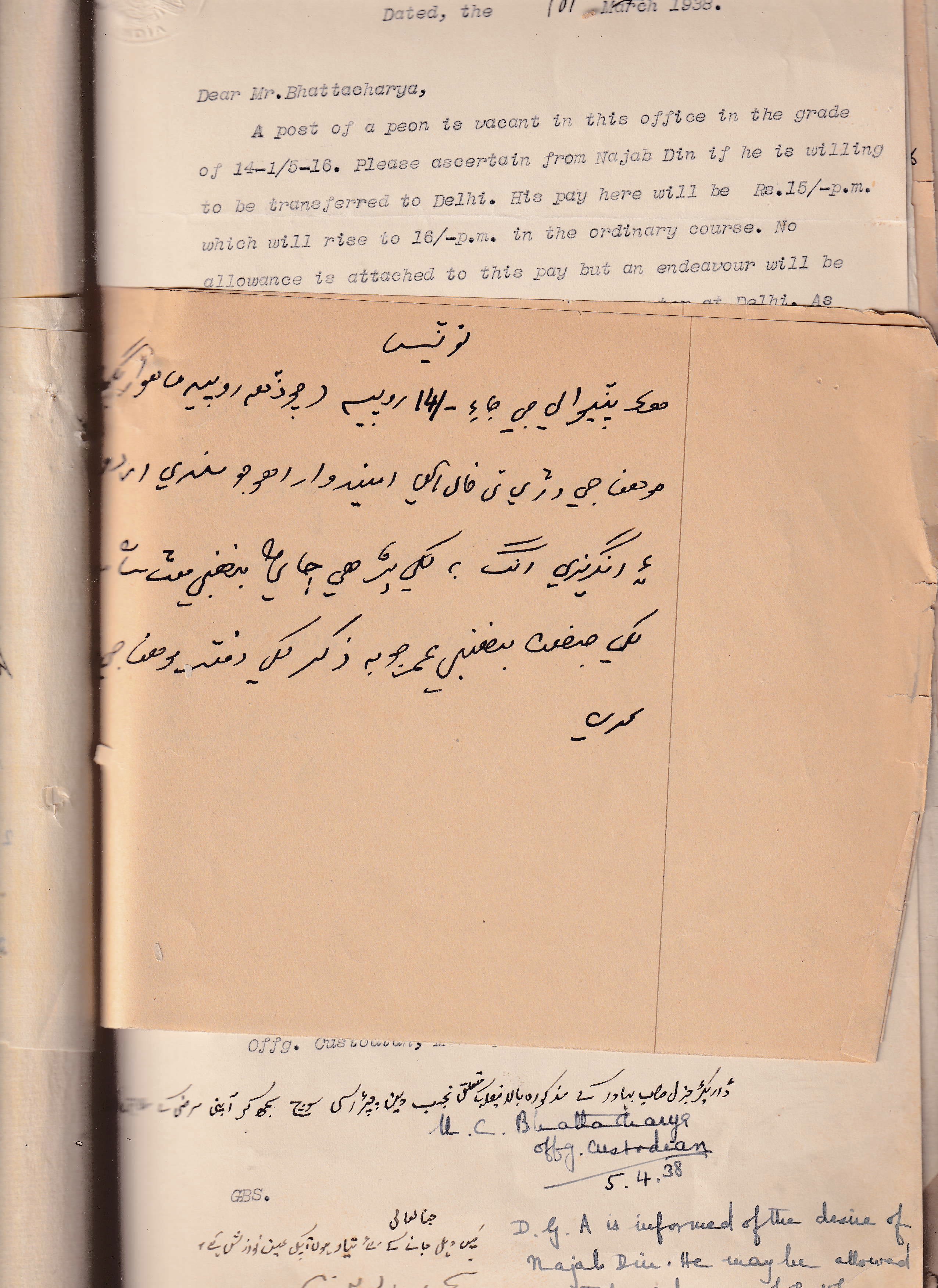

March, 1938

A letter from Najab Din requesting to be paid Rs.14 as he can speak Sindhi, Urdu, and English.

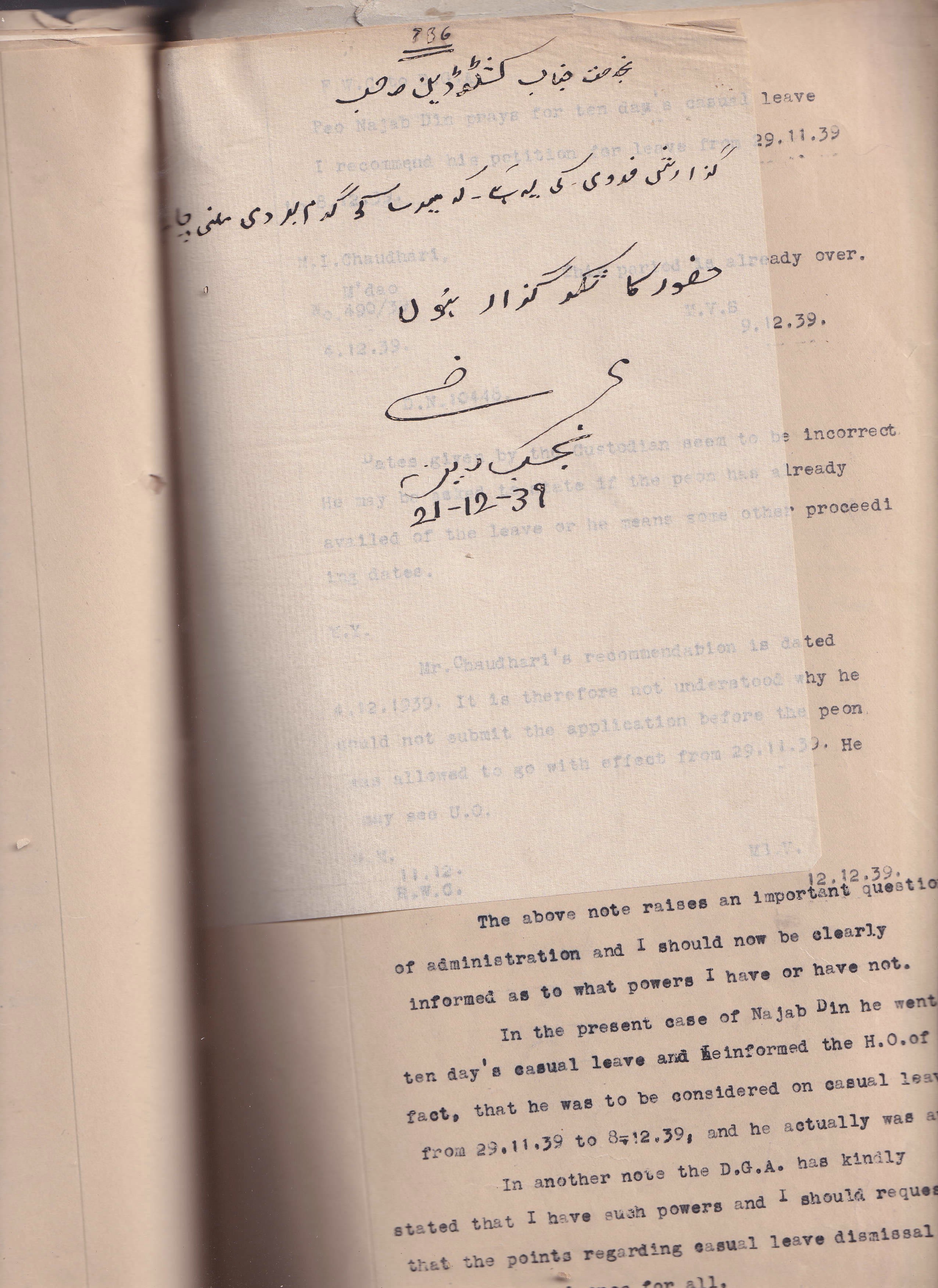

December 12, 1939

To the Custodian:

I would be much obliged if you could provide warm clothing.

From: Najab Din

Najab Din comes from Ambala, a town in pre-partition Punjab (currently a town in Haryana, India). The Ambala Army Cantonment was establish in 1843 by the British Army. It is also the oldest and largest air force base that was established during the British colonial time periods. The large presence of British folks in Najab Din's hometown explains his familiarity with English.

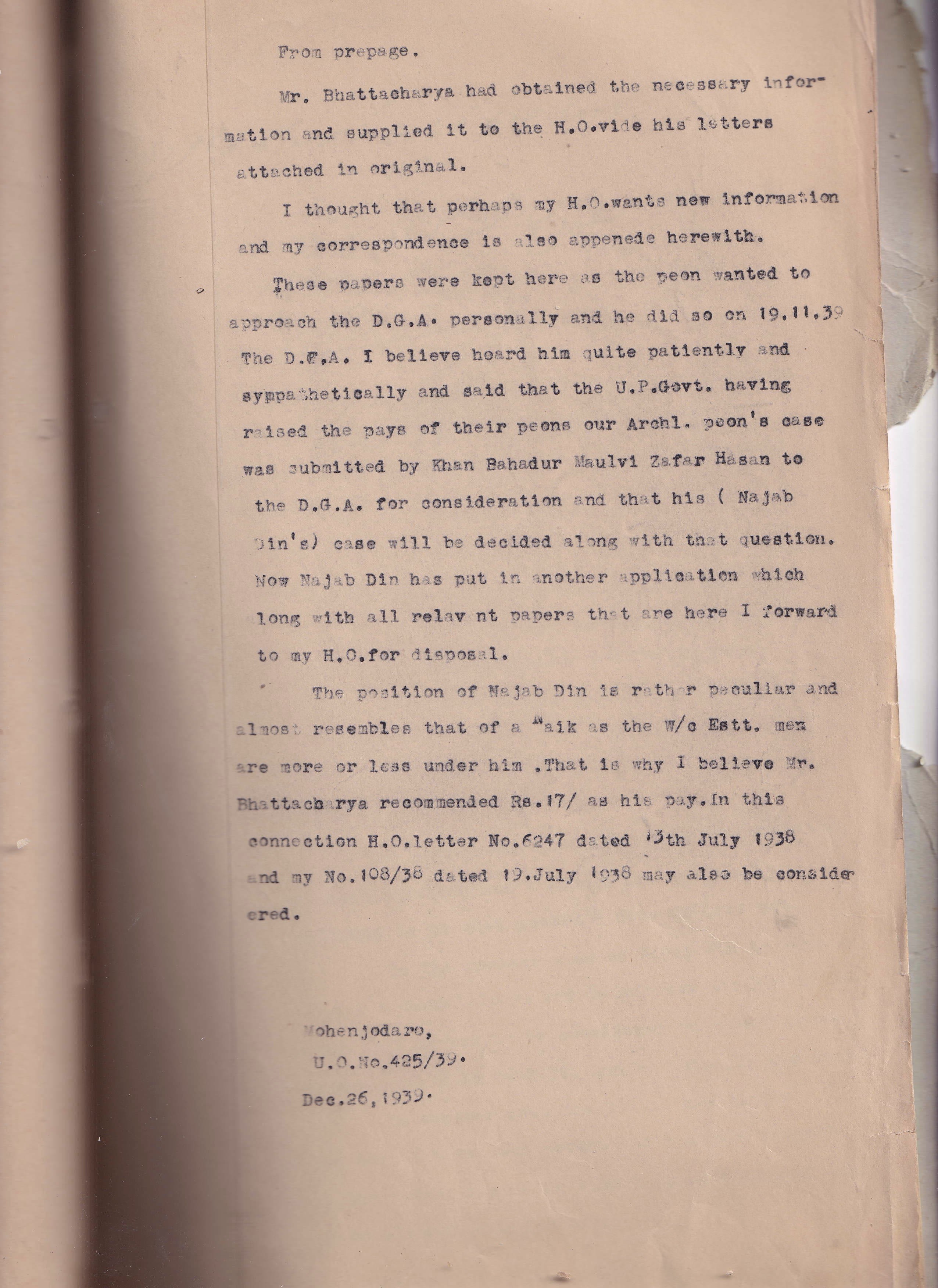

December 26, 1939

... These papers were kept here as the peon wanted to approach the D.G.A. personally and he did so on 19.11.39 The D.G.A. I believe heard him quite patiently and sympathetically and said that the U.P. Govt. having raised the pays of their peons our Archl. peon's case was submitted by Khan Bahadur Maulvi Zafar Hasan to the D.G.A. for consderation and his (Najab Din's) case will be decided along with that question. Now Najab has put in another application which along with all relevant papers that are here I forward to my H.O for disposal.

The position of Najab Din is rather peculiar and almost resembles that of a Naik as the w/c Estt. men and are more or less under him. That is why I believe Mr. Bhattacharya recommended Rs. 17/ as his pay. in this connection H.O. letter No. 6247 dated 13th July 1938 and my No. 108/38 dated ...

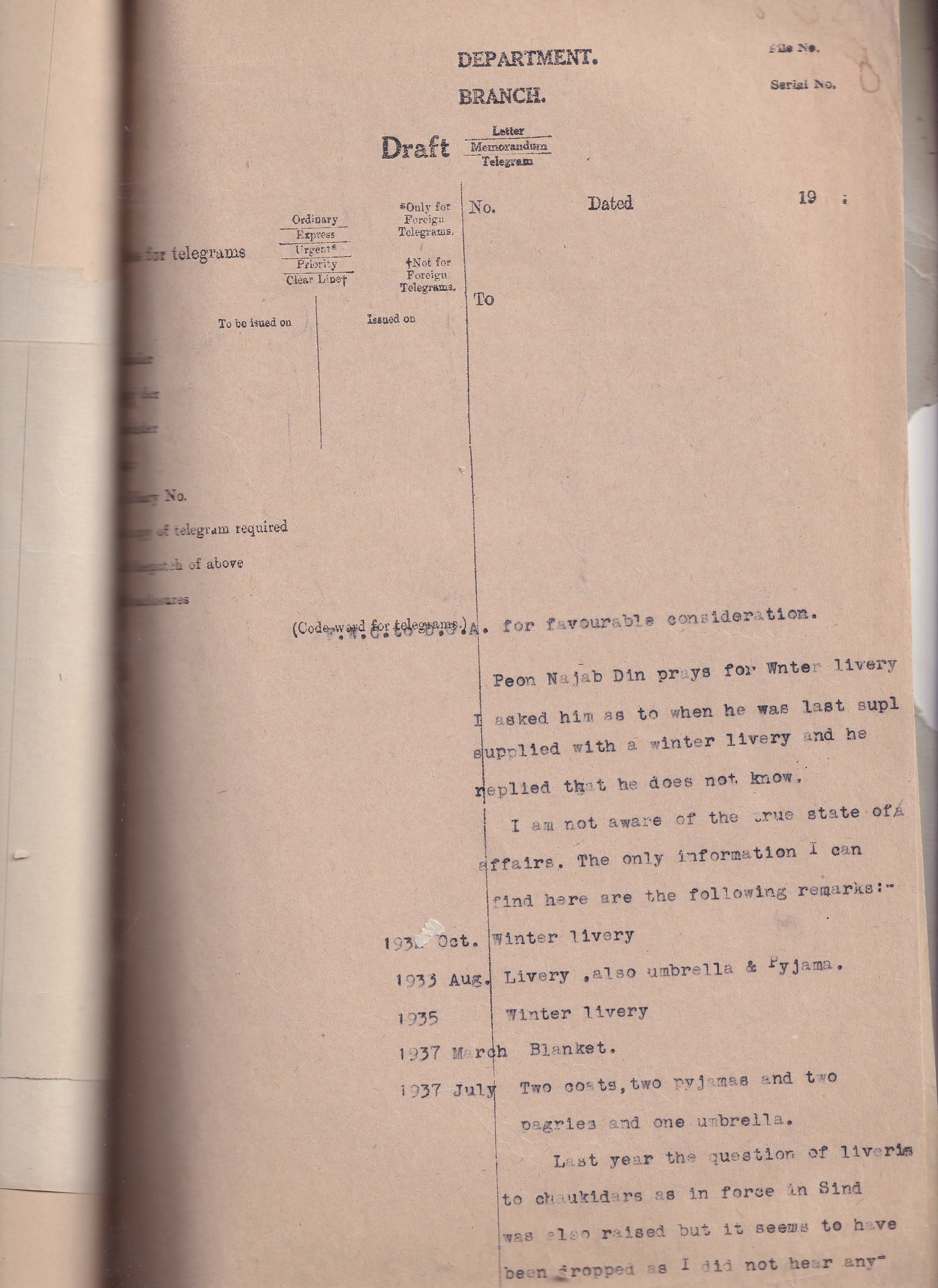

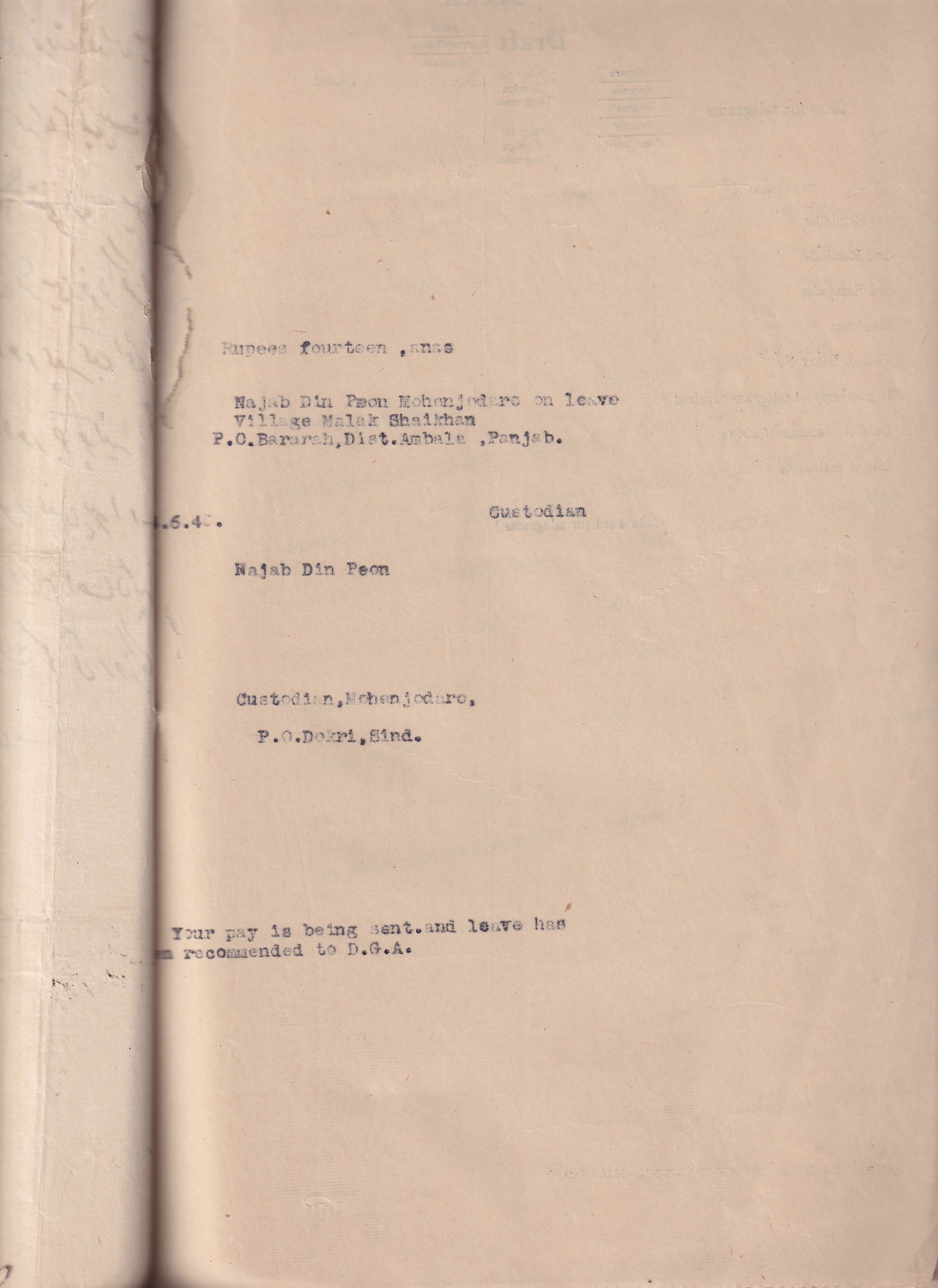

April 10, 1940

D.G.A. for favourable consideration.

Peon Najab Din prays for winter livery I asked him to when he was last supplied with a winter livery and he replied that he does not know.

I am not aware of the true state of affairs. The only information I can find here are the following remarks:

1933 Oct. Winter livery

1933 Aug. Livery, also umbrella & Pyjama.

1935 Winter livery

1937 Blanket.

1937 July Two coats, two pyjamas and two pagries and one umbrella.

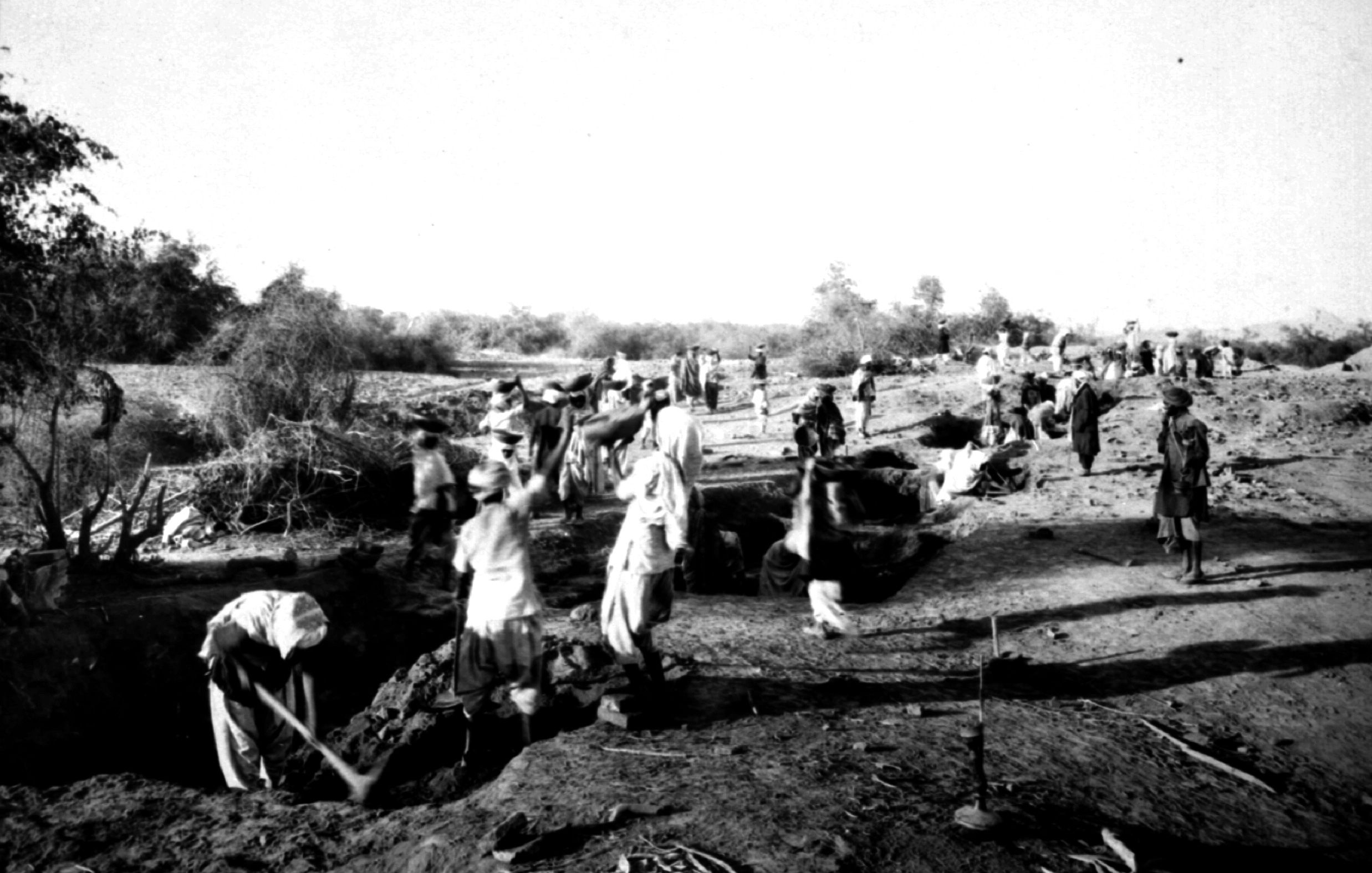

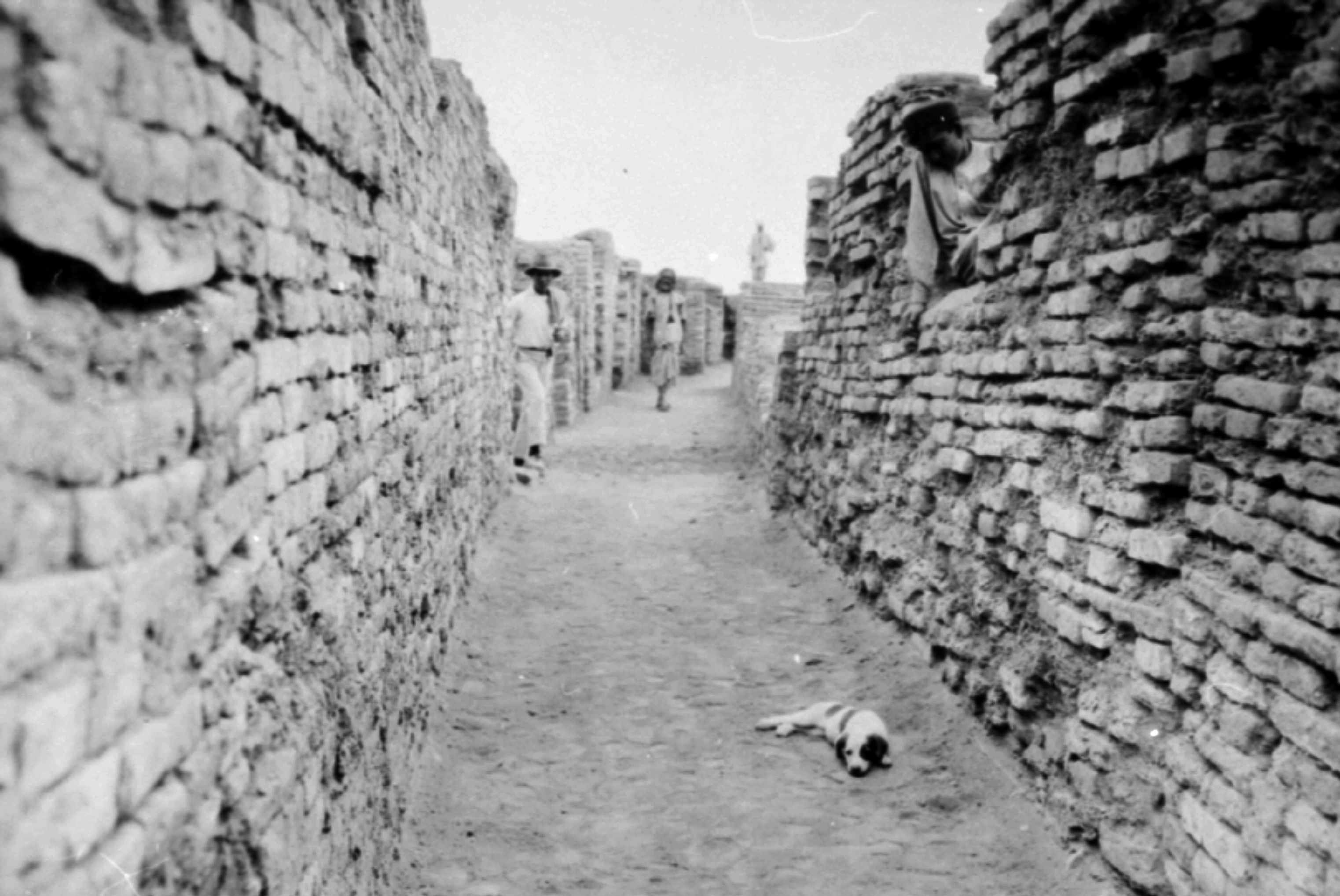

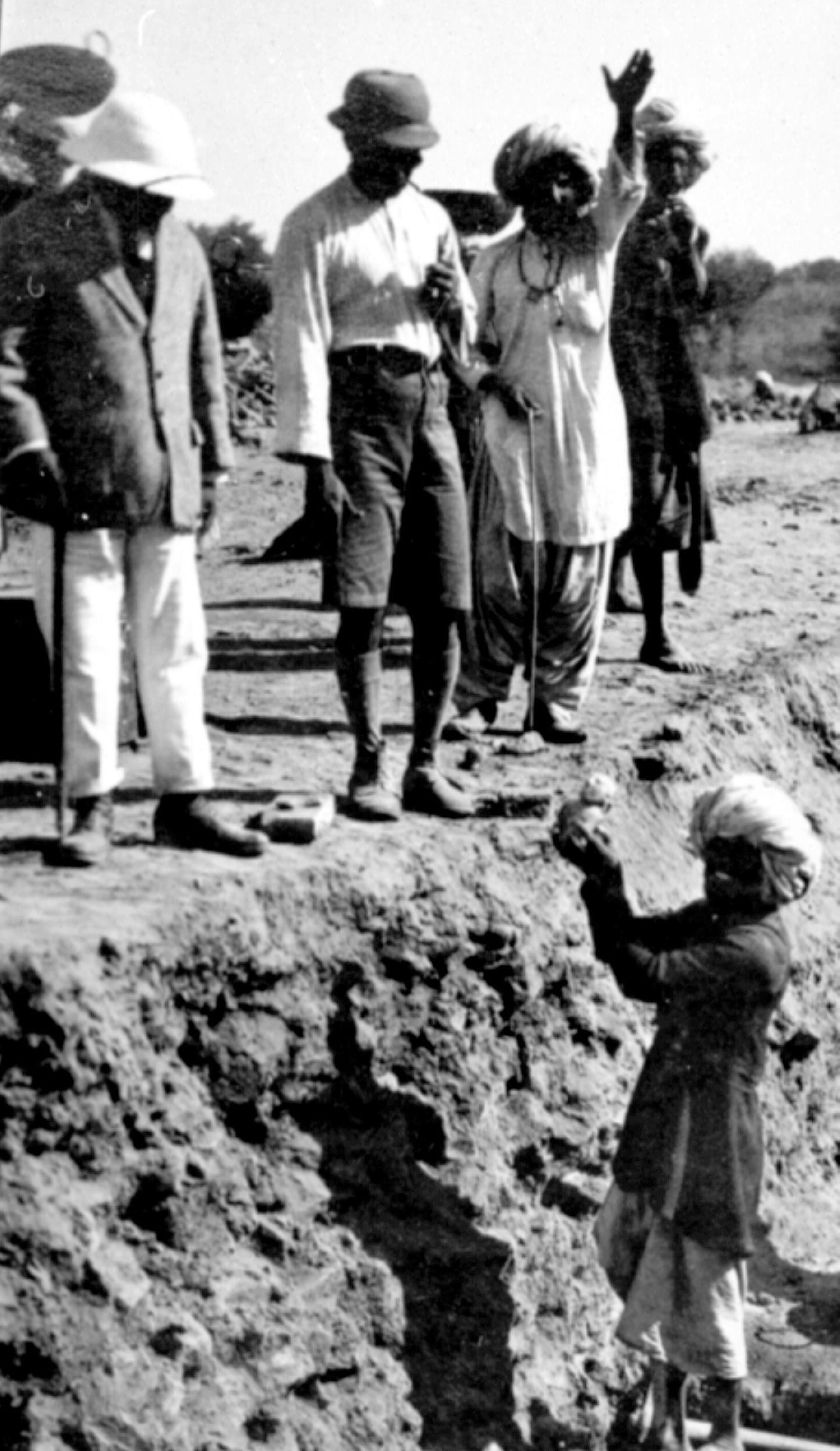

Excavations in DK-G area. Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

Excavations in DK-G area. Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

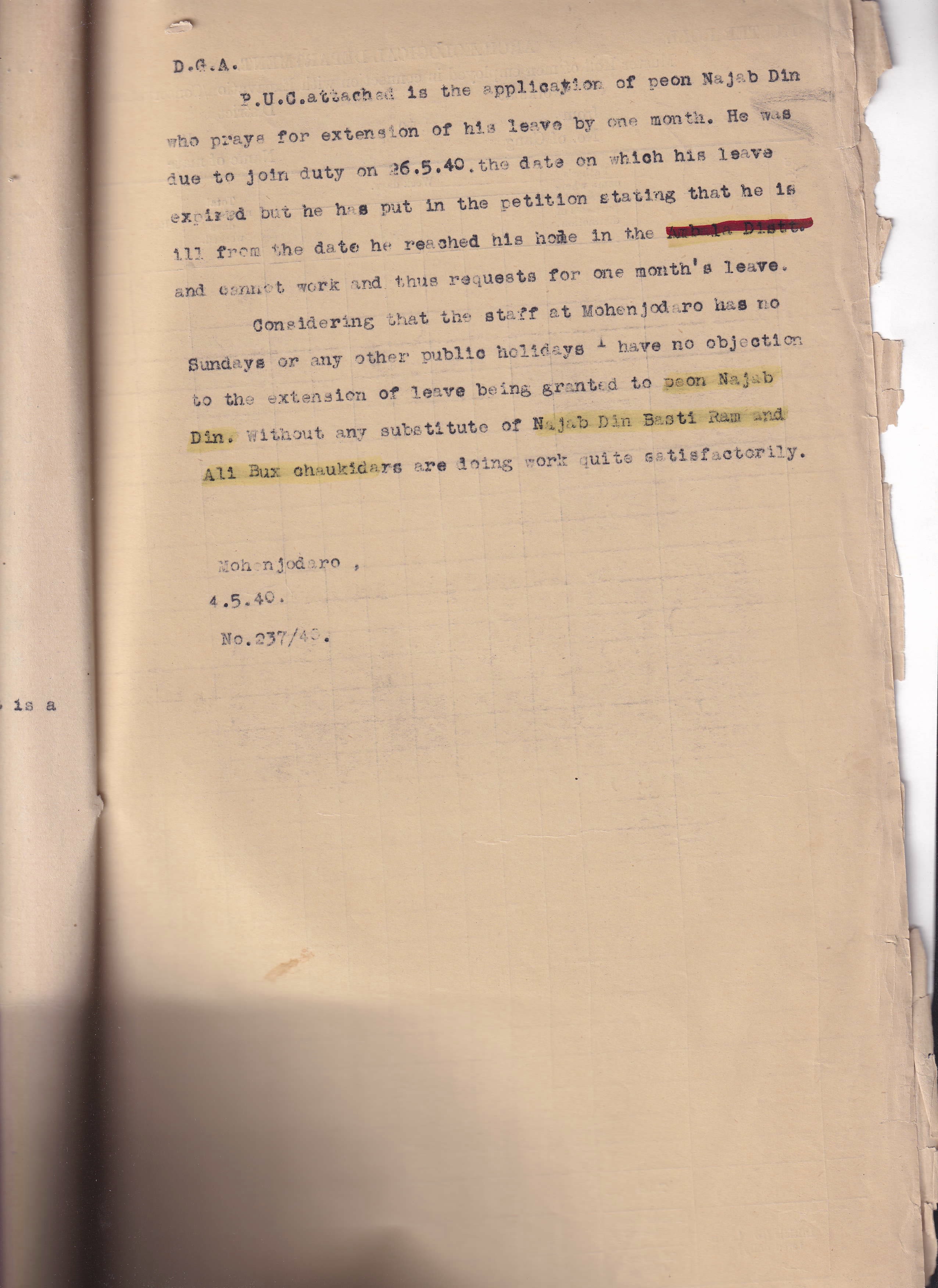

May 4, 1940

…attached is the application of peon Najab Din who prays for extension of his leave by one month…Considering that the staff at Mohenjodaro has no Sundays or any other public holidays I have no objection to the extension…

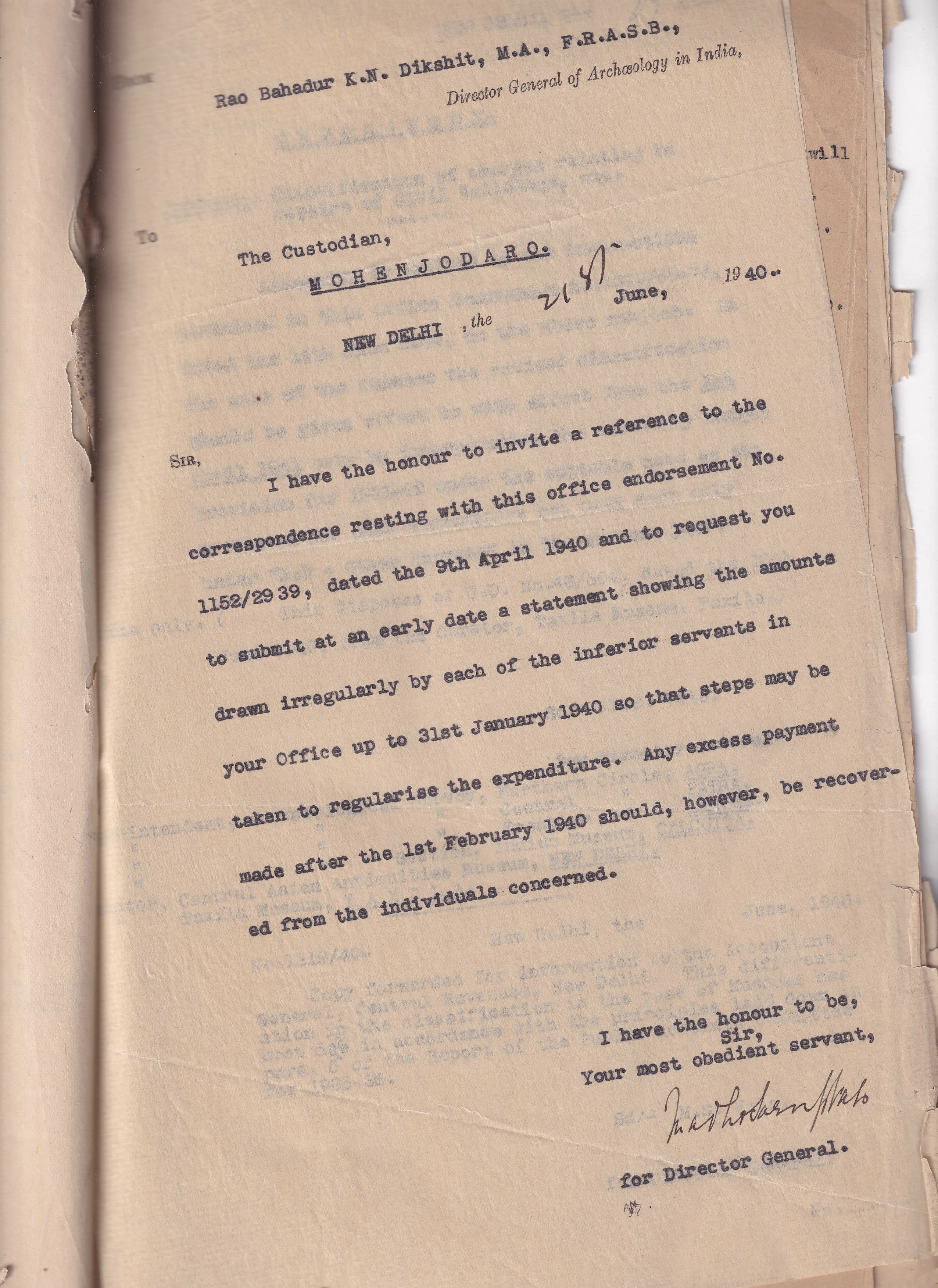

June 21, 1940

Sir,

I have the honour to invite a reference to the correspondence resting with this office endorsement No. 1152/29 39, dated the 9th April 1940 and to request you to submit at an early date a statement showing the amounts drawn irregularly by each of the inferior servants in your Office up to the 31st of January 1940 so that steps may be taken to regularise the expenditure. Any excess payment made after the 1st February 1940 should, however be recovered from the individuals concerned."

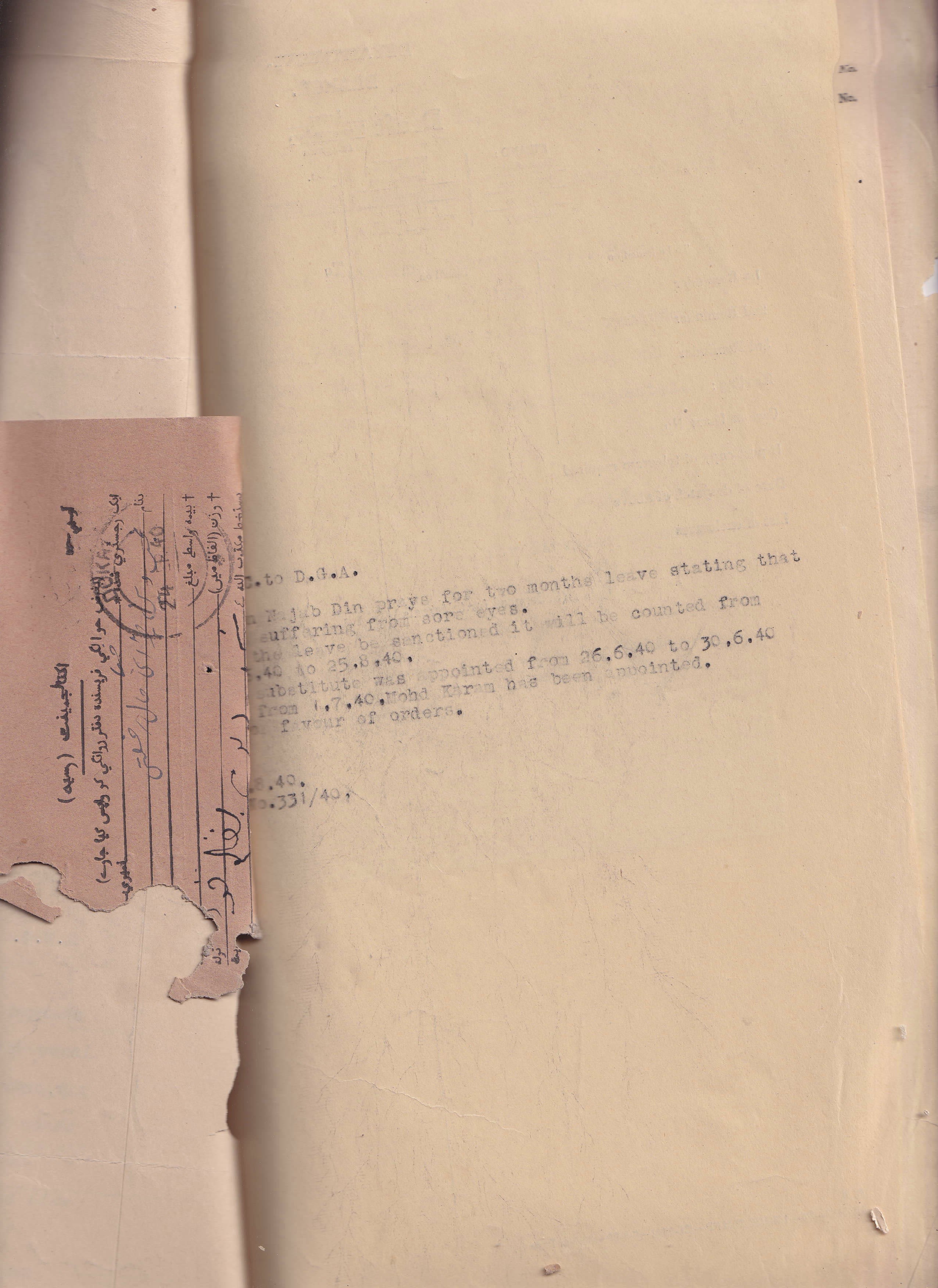

June 25, 1940

to D.G.A.

Najab Din prays for two months leave stating that he is suffering from sore eyes. If the leave will be sanctioned, it will be counted from __,1940 to 25.8.40.

Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

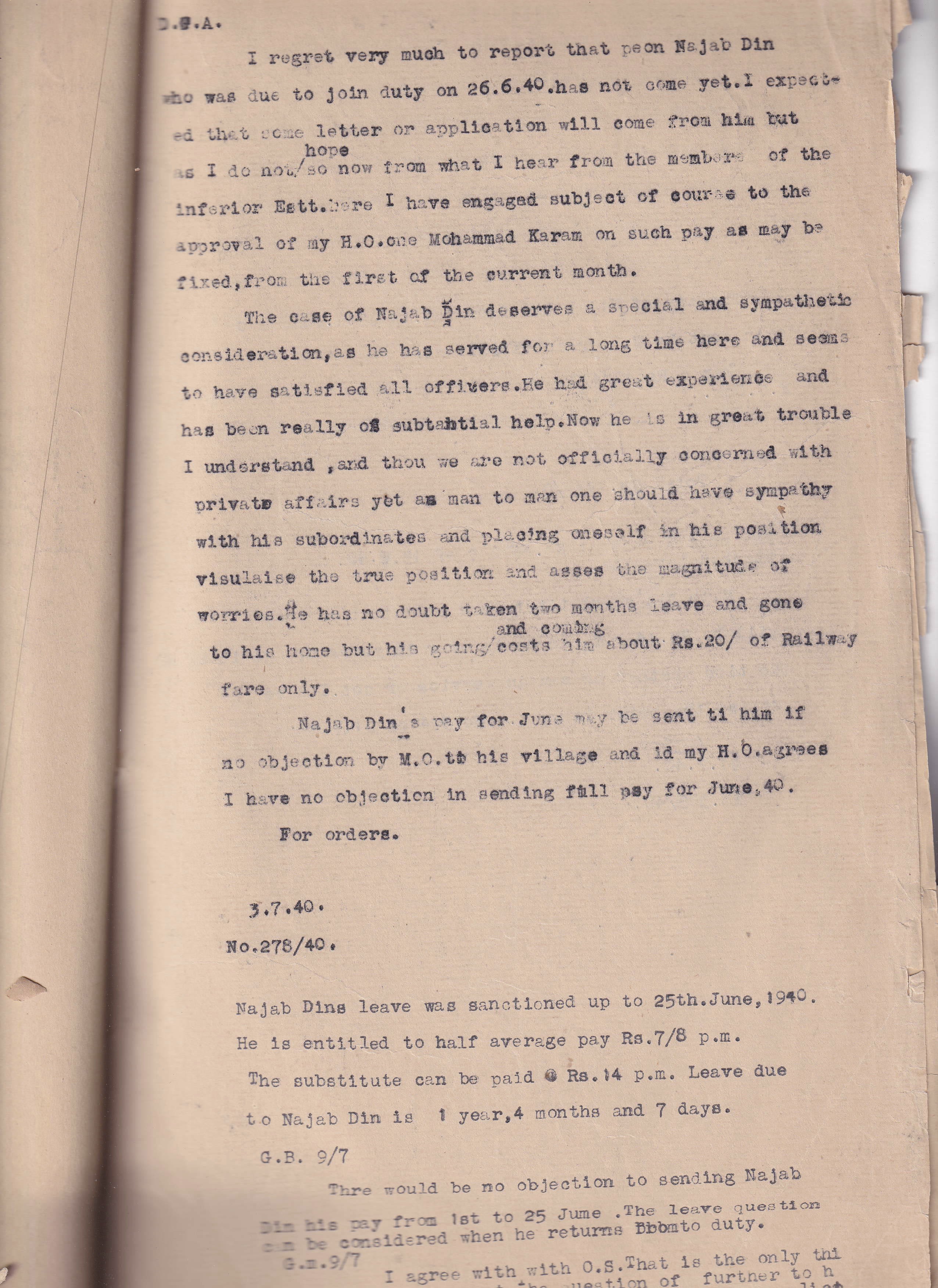

July 3, 1940

Najab Din is meant to have returned from leave on June 6, 1940 but does not show up to work. It's written that other inferior servants are in contact with him, and though the custodian assumed he would receive a letter from Najab Din, talking with the inferior servants changes his expectations.

The case of Najab Din Deserves a special and sympathetic consideration, as he has served for a long time here and seems to have satisfied all officers. He had great experience and has been really of substantial help. Now he is in great trouble I understand, and though we are not officially concerned with private affairs yet as a man to man one should have sympathy with his subordinates and placing oneself in his position visualise the true position and asses [sic] the magnitude of worries. He has no doubt taken two months leave and gone to his home but his going and coming costs him about Rs.20/ of Railway fare only. Najab Din's pay for June may be sent ti [sic] him if no objection by. M.O. to his village and if [sic] my H.O. agrees I have no objection in sending full pay for June, 40.

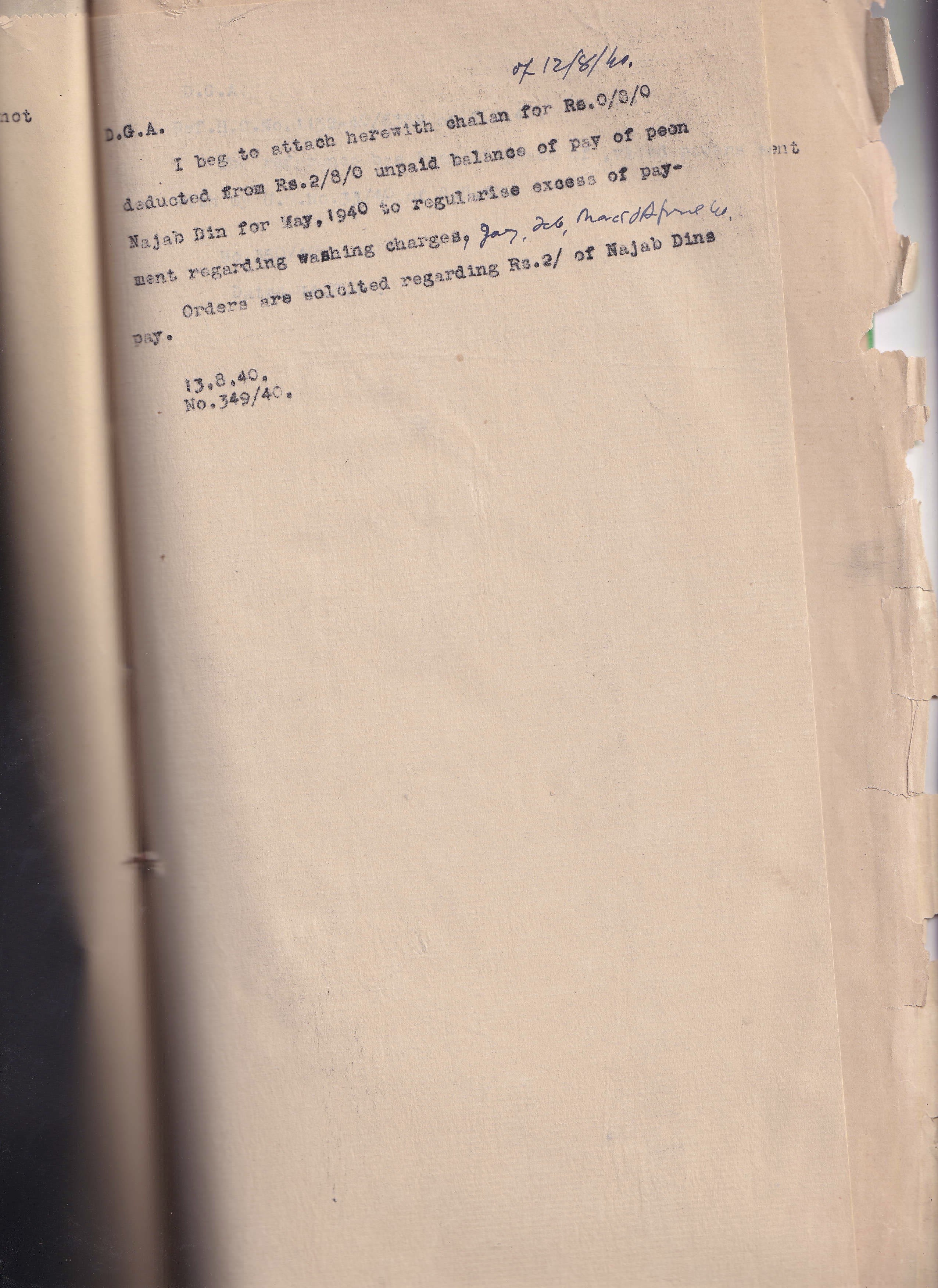

August 13, 1940

I beg to attach herewith chalan for Rs. 0/6/0 deducted from Rs. 2/8/0 unpaid balance of pay of peon Najab Din for May, 1940 to regularise excess of payment regarding washing charges. Orders are solicited regarding Rs.2/ of Najab Dins pay.

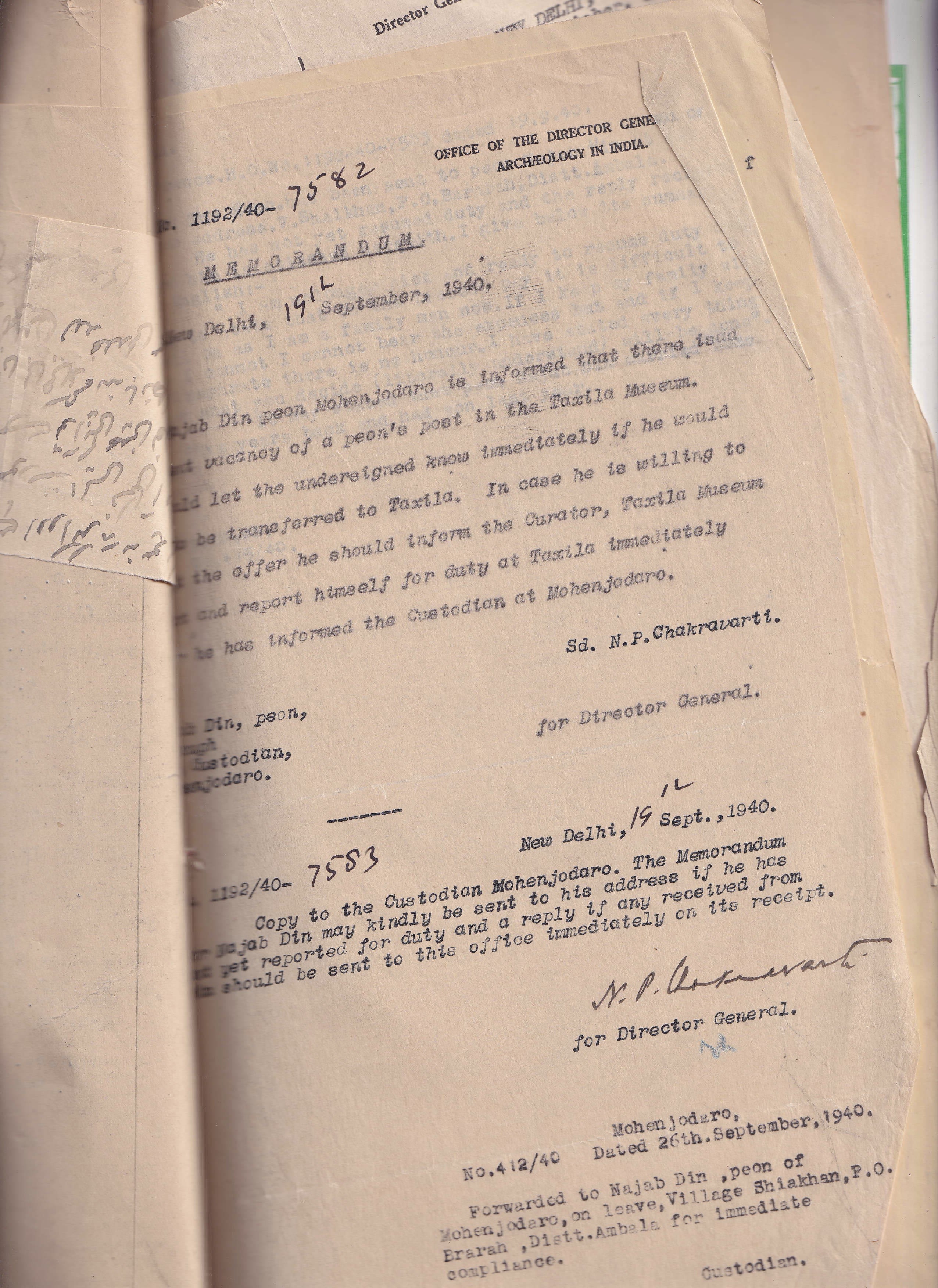

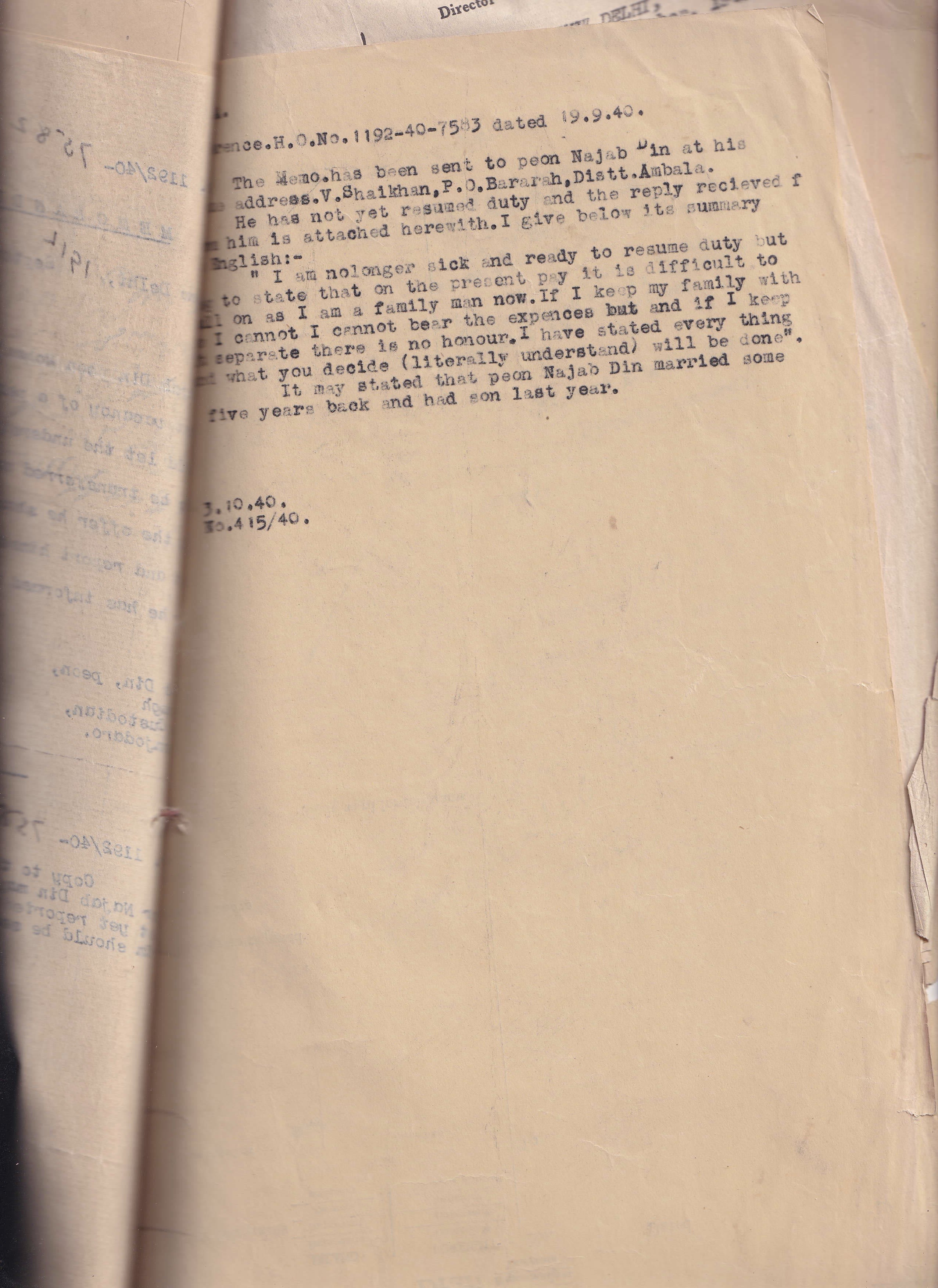

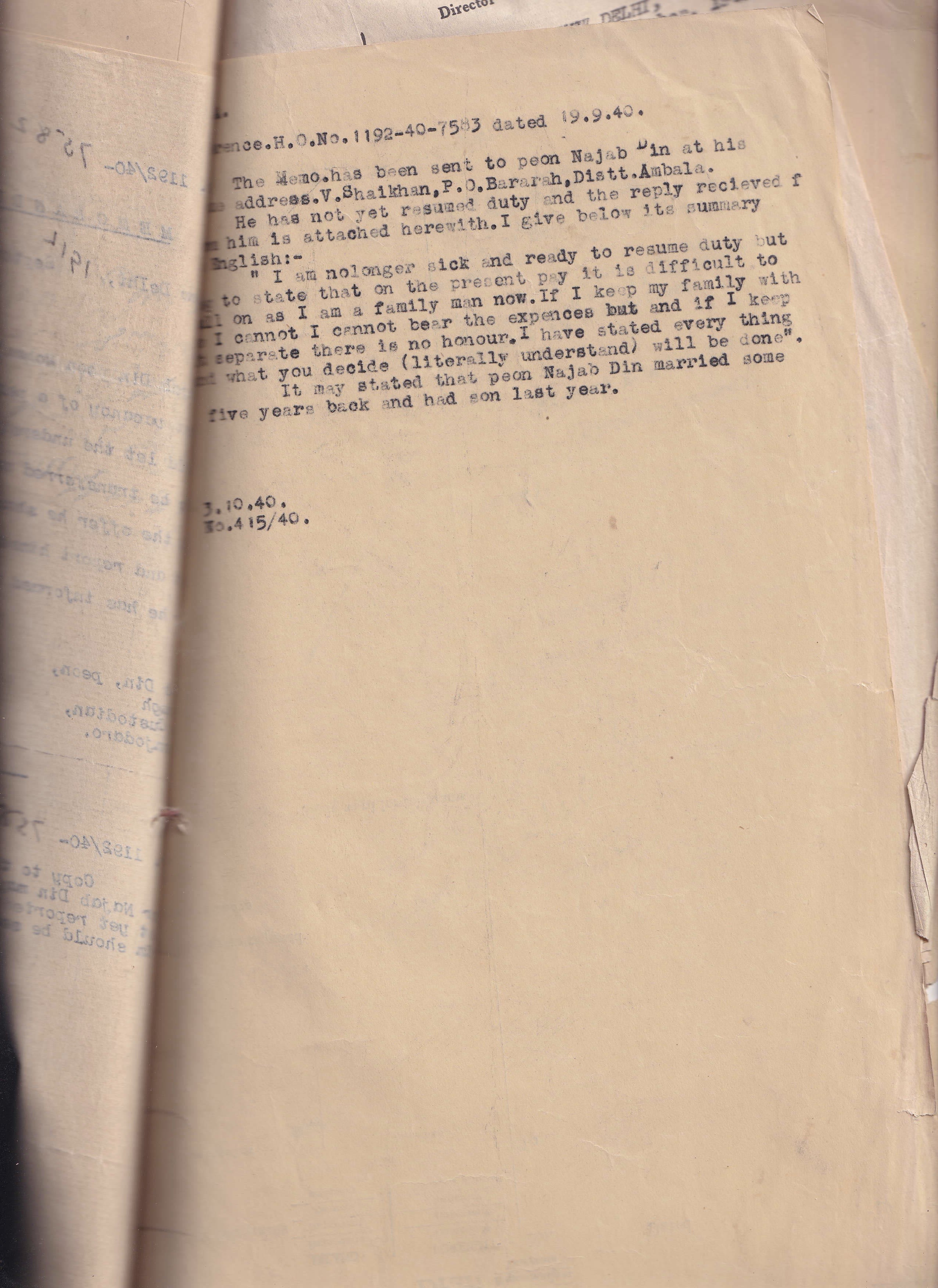

September 19, 1940

Najab Din peon Mohenjodaro is informed that there is a vacancy of a peon's post in the Taxila Museum.

Copy to the Custodian Mohenjodaro. The memorandum for Najab Din may kindly be sent to his address if he has ... not yet reported for duty and a reply if any received should be sent to this office immediately on its receipt.

September 19, 1940

I am no longer sick and ready to resume duty but want to state that on the present pay it is difficult to live on as I am a family man now. If I keep my family with me, I cannot I cannot bear the expenses but and if I keep it separate there is no honour. I have stated everything and what you decide (literally understand) will be done.

It may be noted that peon Najab Din married some five years back and had a son last year.

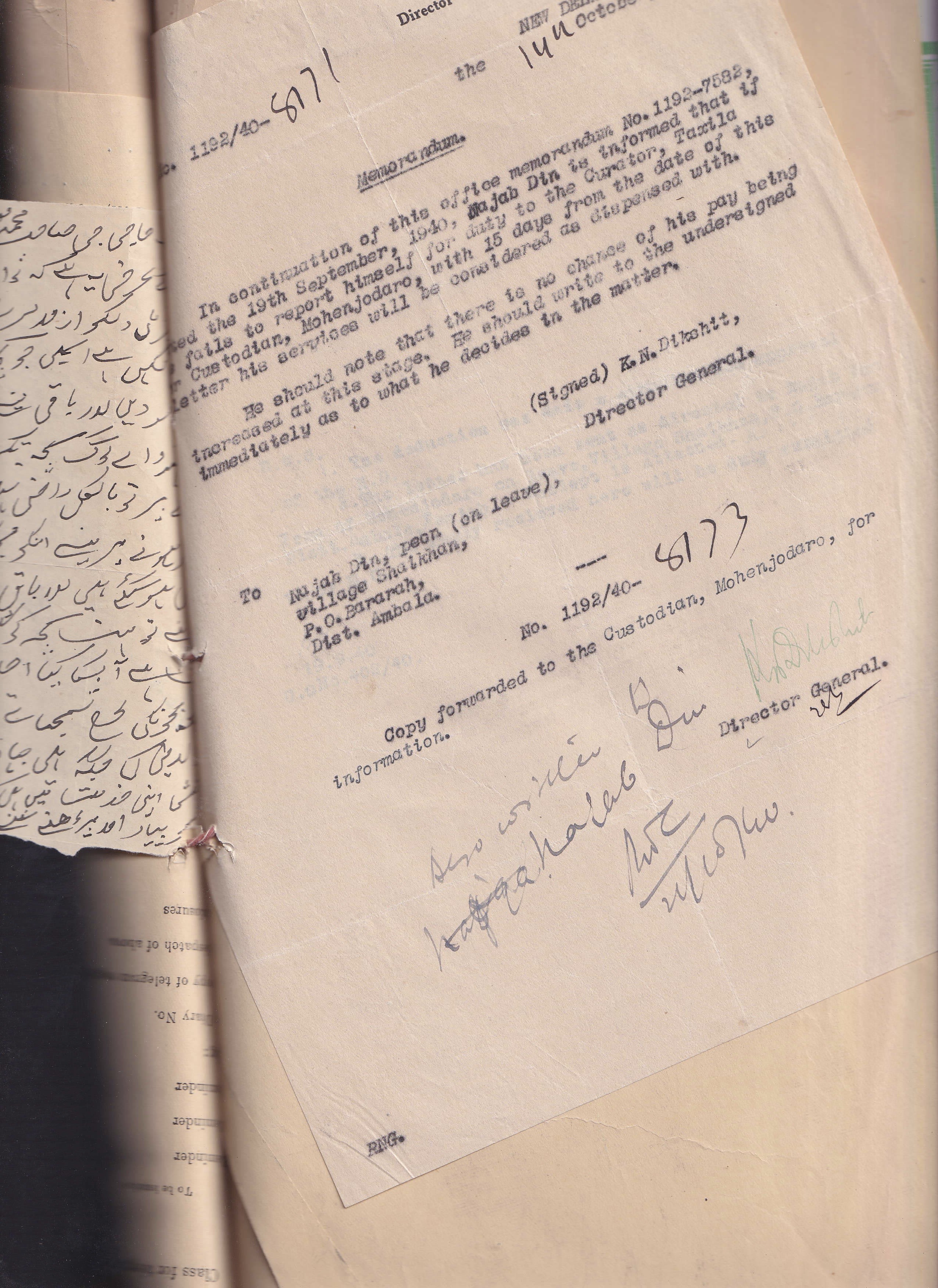

October 14, 1940

In continuation of this office memorandum No. 1192-7852, dated the 19th September, 1940, Najab Din is informed that if he fails to report himself for duty to the Curator, Taxila for Custodian, Mohenjo Daro, with 25 days from the date of this letter his services will be considered as dispensed with.

He should note that there is no chance of his pay being increased at this stage. He should write to the undersigned immediately as to what he decides in the matter.

Excavated lanes in DK-G. Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

Excavated lanes in DK-G. Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

Discovery of the "Priest King" — 1925-26 Season, with K.N. Dikshit. From the collection of Ernest MacKay.

Discovery of the "Priest King" — 1925-26 Season, with K.N. Dikshit. From the collection of Ernest MacKay.

1940

Najab Din's signature for a certified letter sent to him from the Dokri post office.

June 4, 1941

Peon Najab Din is sanctioned a livery.

It does not however appear necessary that an overcoat in addition to the ordinary warm coat should be supplied to a peon. At M.Daro those duties are generally confined to day work. At HQ even the supply of warm coat has been stopped and warm jersies are supplied instead. The supply should be regulated every 3 years and the cost of such livery should not exceed. Rs. 8/10.

1946

Najab Din is listed on a 1946 muster roll as a museum chowkidar with Rs.18 monthly pay.10

Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

Archival images (1927-1931). From the collection of Ernest Mackay.

MohenjoDaro

It often happens

Rivers change course

New cartographies are made

A story forms

Words surface

People are immortalized

It often also happens

That rivers change course

Leaving traces behind

The words lose meaning

Only tales are left

And people lose the story

Poem by Qaiser Abbas, 2012

Translated by Uzma Z. Rizvi, 2023

Acknowledgments

This project the generous support of the following individuals: Syed Sardar Ali Shah, Minister of Culture, Tourism, Antiquities, Government of Sindh (Pakistan), Mr. Manzoor Ahmed Kanasro (Director General of Antiquities, Government of Sindh (Pakistan), Mr. Fateh Shaikh, Ms. Zahida Quadri, Dr. Kaleemullah Lashari, Dr. Asma Ibrahim, Vice Chancellor of Shah Abdul Latif University, Dr. Khalid Ahmed Ibupoto, Dr. G.M. Veesar, Dr. Tasleem Abro, MohenjoDaro Staff, and The Elders of MohenjoDaro

Funding for this project was provided by American Institute of Pakistan Studies (AIPS), Senior

Research Grant 2022-23; Faculty Development Fund 2022-23, Provost’s Office, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY.

End Notes

¹Michael Jansen, “Mohenjo-Daro, Type Site of the Earliest Urbanization Process in South Asia; Ten Years of Research at Mohenjo-Daro, Pakistan and an Attempt at a Synopsis,” in South Asian Archaeology 1993: Proceedings of the Twelfth International conference of the European Association of South Asian Archaeologists held in Helsinki University 5-9 July 1993, eds. Petteri Koskikallio and Asko Parpola (Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1994), 270; Gregory L. Possehl, The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2002), 185; Maurizio Tosi, Luca Bondioli, and Massimo Vidale, “Craft Activity Areas and Surface Survey at MoenjoDaro: Complementary Procedures for the Revaluation of a Restricted Site” in Interim Reports Vol. 1: Reports on Field Work Carried out at Mohenjo-Daro, Pakistan 1982-83, eds. Michael Jansen and Günter Urban (Aachen and Rome: Rheinish-Westf¨alische Technische, Hochschule [RWTH] Aachen, and Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente [sMEO], 1984), 15.

2See also Baird and McFadden, 2014.

3See also Garcia‑Molsosa, et al 2023; Maps were created with QGIS Geographic Information System, http://qgis.osgeo.org; with data and historical maps from the following sources: Geofabrik.“OpenStreetMap.” Pakistan, 2018. https://download.geofabrik.de/asia/pakistan.html; Brown, John. “63k/50k Maps of South Asia,” September 30, 2023. https://zenodo.org/records/7416552

4Banerji, R. D. 1921. “Muhen-jo-daro. Progress reports of the Archaeological Survey of India Western Circle, for the year ending 31 March 1920: 79-80.” Government Central Press, Government of Bombay, General Department; Hussain, M. 1989. “Salvage excavation at Moenjodaro.” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. XXXVII: 89-98; Mackay, Earnest J. H. 1938. “Further Excavations at Mohenjo-daro.” New Delhi. Government of India; Marshall, John H. “1925-26. Excavations at Mohenjo-daro: Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India.” London. Government of India. 72-93; Wheeler, M. 1953. “The Indus Civilization. The Cambridge History of India, Supplementary Volume.” Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

5Jansen, Michaël. 1989. Water supply and sewage disposal at Mohenjo-Daro. World Archaeology: The Archaeology of Public Health, 21(2): 177.

6Haider, Zain. 2023. “DKG South Drone Footage.” Ed. Zeynep Deniz Cavdir. 1: 36 ©LIAHV 2023; Mackay, Earnest J. H. (1937). “Low Lane; East of Blocks 4 and 7.Inter III Level, From North” Plate XXX; "First Street: To Suggest Its Ancient Population from South” Plate XXIV; “Excavation of House 1, Block 7. From South East” Plate LI; “First Street, Late III Draining System From North” Plate XLIV; Further Excavations in Mohenjo-Daro, Volume 2. New Delhi. Director General Archaeological Survey of India.

7Lahiri, Nayanjot. 2005. “Finding Forgotten Cities – How the Indus Civilization was Discovered.” London. Seagull Books.

8Avikunthak, Ashish. 2021. “Bureaucratic Archaeology: State, Science, and Past in Postcolonial India.” Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

9DeSousa, Valerian. 2010. "Modernizing the Colonial Labor Subject in India." Comparative Literature and Culture, 12(2): 1-11.

10The archival labor documents featured are from the Offices of the Director, MohenjoDaro. The captions include text that have corrected spelling errors for clarity.

Works Cited

Avikunthak, Ashish. 2021. “Bureaucratic Archaeology: State, Science, and Past in Postcolonial India.” Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Baird, Jennifer A and Lesley McFadden. 2014. “Towards an archaeology of archaeological archives.” Archaeological Review from Cambridge 29:2.

Banerji, R. D. 1921. “Muhen-jo-daro. Progress reports of the Archaeological Survey of India Western Circle, for the year ending 31 March 1920: 79-80.” Government Central Press, Government of Bombay, General Department.

Brown, John. “63k/50k Maps of South Asia,” September 30, 2023. https://zenodo.org/records/7416552.

DeSousa, Valerian. 2010. "Modernizing the Colonial Labor Subject in India." Comparative Literature and Culture, 12(2): 1-11.

Garcia‑Molsosa, Arnau, Hector A. Orengo, and Cameron A. Petrie. 2023.“Reconstructing long‑term settlement histories on complex alluvial floodplains by integrating historical map analysis and remote‑sensing: an archaeological analysis of the landscape of the Indus River Basin.” Heritage Science, 11:141.

Geofabrik. “OpenStreetMap.” Pakistan, 2018. September 30, 2023. https://download.geofabrik.de/asia/pakistan.html.

Haider, Zain. 2023. “DKG South Drone Footage.” Edited by Zeynep Deniz Cavdir. 1:36. ©LIAHV 2023.

Hussain, M. 1989. “Salvage excavation at Moenjodaro.” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. XXXVII: 89-98.

Jansen, Michael. “Mohenjo-Daro, Type Site of the Earliest Urbanization Process in South Asia; Ten Years of Research at Mohenjo-Daro, Pakistan and an Attempt at a Synopsis.” In South Asian Archaeology 1993: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference of the European Association of South Asian Archaeologists Held in Helsinki University 5-9 July 1993, edited by Petteri Koskikallio and Asko Parpola, 263–80. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1994.

Jansen, Michaël. 1989. Water supply and sewage disposal at Mohenjo-Daro. World Archaeology: The Archaeology of Public Health, 21(2): 177-192.

Lahiri, Nayanjot. 2005. “Finding Forgotten Cities – How the Indus Civilization was Discovered.” London. Seagull Books.

Mackay, Earnest J. H. 1938. “Further Excavations at Mohenjo-daro.” New Delhi. Government of India.

Mackay, Earnest J. H. “1928-29. Excavations at Mohenjo-daro. Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India.” London. Government of India. 67-75.

Marshall, John H. “1925-26. Excavations at Mohenjo-daro: Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India.” London. Government of India. 72-93.

Possehl, G. L. 2002. The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Tosi, Maurizio, Luca Bondioli, and Massimo Vidale. “Craft Activity Areas and Surface Survey at Moenjodaro: Complementary Procedures for the Revaluation of a Restricted Site.” In Interim Reports Vol. 1: Reports on Field Work Carried out at Mohenjo-Daro, Pakistan 1982-83, edited by Michael Jansen and Günter Urban. Aachen: IsMEO-Aachen University Mission, IsMEO/RWTH, 9–38.

Wheeler, M. 1953. “The Indus Civilization. The Cambridge History of India, Supplementary Volume.” Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.